Discover Statecraft

Statecraft

Statecraft

Author: Santi Ruiz

Subscribed: 94Played: 1,936Subscribe

Share

© Santi Ruiz

Description

66 Episodes

Reverse

Today we’re joined by Scott Kupor, Director of the Office of Personnel Management. I think of it as the federal HR department — he makes a compelling case that it’s really the government’s talent management organization.Scott manages talent for an organization of 2+ million people with a $7 trillion budget. We discuss:* How DOGE cut federal headcount — and what comes next?* Why agencies rehired employees they had just laid off* How few federal employees get fired for poor performance* What OPM can do without congressional helpFor the full transcript of this conversation, go to www.statecraft.pub. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.statecraft.pub

CHIPS, the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors Act, is another. It spurred a massive investment boom in semiconductors on American soil, led by the CHIPS Program Office (CPO) at the Department of Commerce. The CPO had to decide how to allocate $39 billion in manufacturing incentives—and then negotiate the details with some of the world's biggest companies.Today, I’m lucky to have on three of the founding members of the CHIPS Program Office team:* Mike Schmidt, the inaugural Director,* Todd Fisher, the Chief Investment Officer, and* Sara Meyers, Chief of Staff and Chief Operating Officer.Mike, Todd, and Sara have a clear sense of what went right for them, what went wrong, and what they’d do differently the next time. In a new project for IFP called Factory Settings, they describe what they learned.The full transcript for this conversation is at www.statecraft.pub. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.statecraft.pub

If you’re a scientist, and you apply for federal research funding, you’ll ask for a specific dollar amount. Let’s say you’re asking for a million-dollar grant. Your grant covers the direct costs, things like the salaries of the researchers that you’re paying. If you get that grant, your university might get an extra $500,000. That money is called “indirect costs,” but think of it as overhead: that money goes to lab space, to shared equipment, and so on.This is the system we’ve used to fund American research infrastructure for more than 60 years. But earlier this year, the Trump administration proposed capping these payments at just 15% of direct costs, way lower than current indirect cost rates. There are legal questions about whether the admin can do that. But if it does, it would force universities to fundamentally rethink how they do science.The indirect costs system is pretty opaque from the outside. Is the admin right to try and slash these indirect costs? Where does all that money go? And if we want to change how we fund research overhead, what are the alternatives? How do you design a research system to incentivize the research you actually wanna see in the world?I’m joined today by Pierre Azoulay from MIT Sloan and Dan Gross from Duke’s Fuqua School of Business. Together with Bhaven Sampat at Johns Hopkins, they conducted the first comprehensive empirical study of how indirect costs actually work. Earlier this year, I worked with them to write up that study as a more accessible policy brief for IFP. They’ve assembled data on over 350 research institutions, and they found some striking results. While negotiated rates often exceed 50-60%, universities actually receive much less, due to built-in caps and exclusions.Moreover, the institutions that would be hit hardest by proposed cuts are those whose research most often leads to new drugs and commercial breakthroughs.Thanks to Katerina Barton, Harry Fletcher-Wood, and Inder Lohla for their help with this episode, and to Beez for her help on the charts.Let’s say I’m a researcher at a university and I apply for a federal grant. I’m looking at cancer cells in mice. It will cost me $1 million to do that research — to pay grad students, to buy mice and test tubes. I apply for a grant from the National Institutes of Health, or NIH. Where do indirect costs come in?Dan Gross: Research generally incurs two categories of costs, much as business operations do.* Direct or variable costs are typically project-specific; they include salaries and consumable supplies.* Indirect or fixed costs are not as easily assigned to any particular project. [They include] things like lab space, data and computing resources, biosecurity, keeping the lights on and the buildings cooled and heated — even complying with the regulatory requirements the federal government imposes on researchers. They are the overhead costs of doing research.Pierre Azoulay: You will use those grad students, mice, and test tubes, the direct costs. But you’re also using the lab space. You may be using a shared facility where the mice are kept and fed. Pieces of large equipment are shared by many other people to conduct experiments. So those are fixed costs from the standpoint of your research project.Dan: Indirect Cost Recovery (ICR) is how the federal government has been paying for the fixed cost of research for the past 60 years. This has been done by paying universities institution-specific fixed percentages on top of the direct cost of the research. That’s the indirect cost rate. That rate is negotiated by institutions, typically every two to four years, supported by several hundred pages of documentation around its incurred costs over the recent funding cycle.The idea is to compensate federally funded researchers for the investments, infrastructure, and overhead expenses related to the research they perform for the government. Without that funding, universities would have to pay those costs out of pocket and, frankly, many would not be interested or able to do the science the government is funding them to do.Imagine I’m doing my mouse cancer science at MIT, Pierre’s parent institution. Some time in the last four years, MIT had this negotiation with the National Institutes of Health to figure out what the MIT reimbursable rate is. But as a researcher, I don’t have to worry about what indirect costs are reimbursable. I’m all mouse research, all day.Dan: These rates are as much of a mystery to the researchers as it is to the public. When I was junior faculty, I applied for an external grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) — you can look up awards folks have won in the award search portal. It doesn’t break down indirect and direct cost shares of each grant. You see the total and say, “Wow, this person got $300,000.” Then you go to write your own grant and realize you can only budget about 60% of what you thought, because the rest goes to overhead. It comes as a bit of a shock the first time you apply for grant funding.What goes into the overhead rates? Most researchers and institutions don’t have clear visibility into that. The process is so complicated that it’s hard even for those who are experts to keep track of all the pieces.Pierre: As an individual researcher applying for a project, you think about the direct costs of your research projects. You’re not thinking about the indirect rate. When the research administration of your institution sends the application, it’s going to apply the right rates.So I’ve got this $1 million experiment I want to run on mouse cancer. If I get the grant, the total is $1.5 million. The university takes that .5 million for the indirect costs: the building, the massive microscope we bought last year, and a tiny bit for the janitor. Then I get my $1 million. Is that right?Dan: Duke University has a 61% indirect cost rate. If I propose a grant to the NSF for $100,000 of direct costs — it might be for data, OpenAI API credits, research staff salaries — I would need to budget an extra $61,000 on top for ICR, bringing the total grant to $161,000.My impression is that most federal support for research happens through project-specific grants. It’s not these massive institutional block grants. Is that right?Pierre: By and large, there aren’t infrastructure grants in the science funding system. There are other things, such as center grants that fund groups of investigators. Sometimes those can get pretty large — the NIH grant for a major cancer center like Dana-Farber could be tens of millions of dollars per year.Dan: In the past, US science funding agencies did provide more funding for infrastructure and the instrumentation that you need to perform research through block grants. In the 1960s, the NSF and the Department of Defense were kicking up major programs to establish new data collection efforts — observatories, radio astronomy, or the Deep Sea Drilling project the NSF ran, collecting core samples from the ocean floor around the world. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) — back then the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) — was investing in nuclear test detection to monitor adherence to nuclear test ban treaties. Some of these were satellite observation methods for atmospheric testing. Some were seismic measurement methods for underground testing. ARPA supported the installation of a network of seismic monitors around the world. Those monitors are responsible for validating tectonic plate theory. Over the next decade, their readings mapped the tectonic plates of the earth. That large-scale investment in research infrastructure is not as common in the US research policy enterprise today.That’s fascinating. I learned last year how modern that validation of tectonic plate theory was. Until well into my grandparents’ lifetime, we didn’t know if tectonic plates existed.Dan: Santi, when were you born?1997.Dan: So I’m a good decade older than you — I was born in 1985. When we were learning tectonic plate theory in the 1990s, it seemed like something everybody had always known. It turns out that it had only been known for maybe 25 years.So there’s this idea of federal funding for science as these massive pieces of infrastructure, like the Hubble Telescope. But although projects like that do happen, the median dollar the Feds spend on science today is for an individual grant, not installing seismic monitors all over the globe.Dan: You applied for a grant to fund a specific project, whose contours you’ve outlined in advance, and we provided the funding to execute that project.Pierre: You want to do some observations at the observatory in Chile, and you are going to need to buy a plane ticket — not first class, not business class, very much economy.Let’s move to current events. In February of this year, the NIH announced it was capping indirect cost reimbursement at 15% on all grants.What’s the administration’s argument here?Pierre: The argument is there are cases where foundations only charge 15% overhead rate on grants — and universities acquiesce to such low rates — and the federal government is entitled to some sort of “most-favored nation” clause where no one pays less in overhead than they pay. That’s the argument in this half-a-page notice. It’s not much more elaborate than that.The idea is, the Gates Foundation says, “We will give you a grant to do health research and we’re only going to pay 15% indirect costs.” Some universities say, “Thank you. We’ll do that.” So clearly the universities don’t need the extra indirect cost reimbursement?Pierre: I think so.Dan: Whether you can extrapolate from that to federal research funding is a different question, let alone if federal research was funding less research and including even less overhead. Would foundations make up some of the difference, or even continue funding as much research, if the resources provided by the federal government were lower? Those are open questions. Foundations complement fede

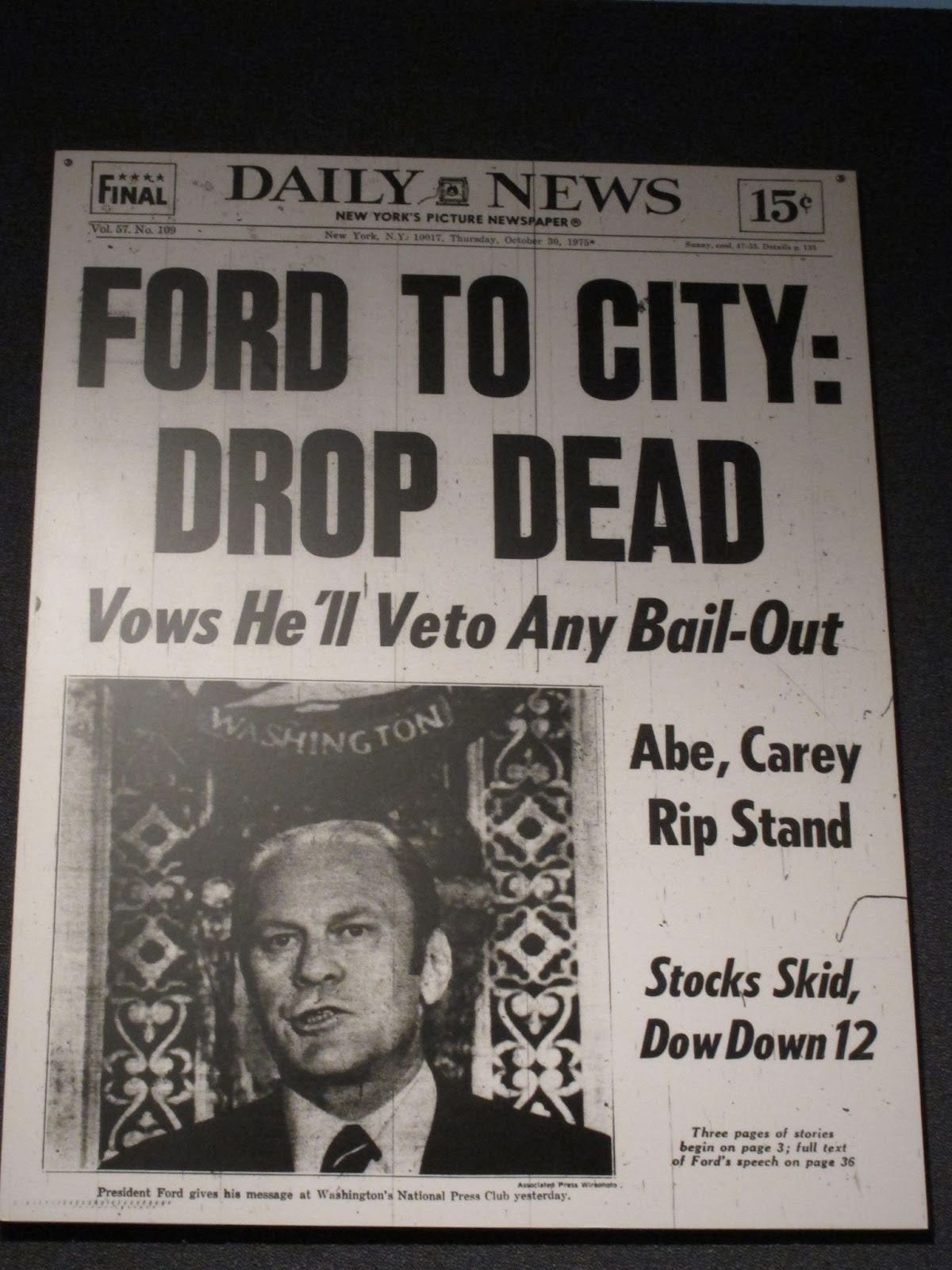

The full transcript for this conversation and many others can be found at www.statecraft.pub.Today we’re joined by David Schleicher. David is Professor of Property and Urban Law at Yale Law School, and an expert in local government law, land use, finance, and urban development.I found David’s book, In a Bad State: Responding to State and Local Budget Crises, a fascinating and readable primer on municipal debt: what it is, how it grows, and how cities can face up to it.Municipal pension funding may not sound like the most fascinating topic. I hope this conversation illustrates two things. First, how our pension systems work matters to all of us — whether or not we are enrolled in a municipal pension. Second, these questions go to the heart of how our cities are run, why they fail, and how they can be improved.We discuss:* Why are so many municipal pension funds in debt?* Why New York City went bankrupt and Chicago didn’t* Moral hazard in municipal credit* The practice of "universal log rolls"* How the federal government should respond to local bankruptcies This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.statecraft.pub

Today we’re joined by Judd Devermont, one of the most experienced Africa policy hands in Washington. He spent 16 years as an intelligence analyst, serving in both the Obama and Biden administrations. Most recently, he was Senior Director for African Affairs at the National Security Council. He authored the Biden administration’s Strategy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa. Since leaving government in early 2024, he writes a newsletter called Post Strategy, reflecting on what works and what doesn’t in US policy toward Africa.We discuss* What “care and feeding” means in diplomacy* What went wrong with the relationships with Niger* The problem with envoys* Whether the NSC has been neutered under Trump* Why most intelligence analysis doesn’t cut it anymoreThe full transcript for this conversation is at www.statecraft.pub. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.statecraft.pub

You can find the full transcript of this conversation at www.statecraft.pub.The likely next mayor of New York City is Zohran Mamdani, if polling is anywhere close to being correct. Much of the conversation has revolved around the day-to-day administration of City Hall. If Mamdani wins, does he have what it takes to run the city’s government?Today’s guest is still active in NYC political life, and it was clear I would not get an answer to that particular question. Instead, I took this opportunity to investigate how City Hall actually runs, and how the past three mayors have structured their administrations. But if you read between the lines, you can treat this conversation as a guide about what has worked in New York’s governance over the last 20 years, and the likely stumbling blocks for an ambitious new administration.Maria Torres-Springer moved to New York City a week before 9/11, and spent most of the following 20 years in city government — first as a top appointee in the Bloomberg administration, then in several high-powered roles under Bill de Blasio, and eventually as second-in-command for Eric Adams. Her most recent role was as first deputy mayor: functionally the Chief Operating Officer of New York City. Torres-Springer resigned in February 2025 (she was not implicated in the overlapping Eric Adams corruption scandals).To put it lightly, Torres-Springer has fans. In November 2024, City & State New York wrote a cover story titled, “The Vibe at City Hall is Thank God for Maria Torres-Springer.” It quotes political figures from the far left, center left, and right, calling Torres-Springer “a phenomenal leader,” “a very classy, charismatic, knowledgeable individual,” and, “a serial overachiever in a good way.” When Adams appointed her as first deputy mayor, he said, “She has the ability of landing the plane.”Torres-Springer is widely described as one of the most effective political operators in New York City, and she’s been linked in media stories as a potential official in the next mayoral administration (although she recently took a role as President of the Revson Foundation, a NYC-based philanthropic organization). She’s maybe the best possible guest to talk about steering City Hall.Given constraints on what Torres-Springer could discuss, I wanted to get into two big topics. One is process. What does it take to run City Hall? How have different mayors done it differently? The other is outcomes. Torres-Springer was one of the champions of City of Yes, the Adams-backed initiative to build 500,000 new housing units in the city over the next 10 years. I wanted to better understand City of Yes, what she’s most excited about, what didn’t make the cut, and how it all came together politically.We discuss:* What it takes to succeed working for three very different mayors* How Bloomberg, de Blasio, and Adams governed differently* How to work effectively under constant pressure* The political coalitions that made City of Yes possible* Why it takes over a year to turn over a NYCHA apartment* How to fix the plumbing of government* What the next mayor should prioritize to keep New York thrivingThanks to Harry Fletcher-Wood, Eamonn Ives, and Katerina Barton for their judicious audio and transcript edits for length and clarity. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.statecraft.pub

This episode was originally recorded on October 18th at the Progress Conference in Berkeley. Because of the federal shutdown, Director Kratsios called in virtually.Michael Kratsios is Director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, and the president’s top science and technology advisor. In the first Trump administration, Kratsios was US Chief Technology Officer, and later acting Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, where he championed emerging tech like AI, quantum, and autonomous systems in defense.Given constraints in the topics Kratsios could speak on, my questions focused on understanding the administration’s AI and science policy. We talked about the recent AI Action Plan: what AI can do for America and the world, and how the administration plans to ensure US leadership. We discuss the administration’s vision for gold standard science, and whether the structures we use to fund science need to change. We also touched on how the second Trump administration differs from the first, and Kratsios’s take on AI safety.Thanks to Harry Fletcher-Wood and Katerina Barton for their light edits for length and clarity in the transcript and audio, respectively, and for a tight turnaround. The White House has not yet cleared the full video for publication, but we’ll share it here if it is cleared.The full transcript for this conversation and many others is available at www.statecraft.pub. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.statecraft.pub

Today we’re talking about housing. The ROAD to Housing Act passed the Senate Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Committee 24-0 in late July. Last week — despite the shutdown — it cleared the Senate. It’s a package of 27 pieces of legislation to boost housing supply, improve affordability, reduce regulatory roadblocks, and reduce homelessness.When you zoom out a bit, what’s happened here is pretty surprising. The chair of the committee, Republican Tim Scott, and the Ranking Member, Elizabeth Warren, a Democrat, co-sponsored the bill. The bill is the committee’s first bipartisan housing markup in over a decade. Passing through committee unanimously doesn’t happen often for serious bills of this sort. I wanted to understand how this bill happened, and came to have a serious shot at passing. And I also wanted to get a better sense of what’s actually in the bill, and why it matters for housing. If you’re like me, most of the debates you hear about housing policy focus on zoning, which is a local issue — very little federal say. So what are all these pieces of legislation? Do they matter?Joining me is an unorthodox trio:* Will Poff-Webster was legislative counsel for Senator Brian Schatz, a Democrat from Hawaii. He’s our inside guy today: he worked on the bill within the Senate. And today, he covers housing policy here at IFP.* Alex Armlovich is Senior Housing Policy Analyst at the Niskanen Center. He has been working on housing issues for a long time, and his fingerprints are on parts of this bill package. He’s my advocate from the outside.* Brian Potter is Senior Infrastructure Fellow at IFP and author of Construction Physics, which I very much enjoy editing. If I can make one newsletter recommendation to you besides Statecraft, it’s Construction Physics. He has a background in private-sector home building. And has written about several of the proposals in this package.Table of contents:* What’s the federal role in housing policy?* What’s in the bill?* Regulatory reform* Technical assistance plus incentives* Funding and financing reform* A brief sidebar on manufactured home chassis* Will the bill matter?* How did the bill happen, politically speaking?* The policy wonk success storyThank you to Harry Fletcher-Wood and Katerina Barton for their judicious transcript and audio edits.For the full transcript of this conversation, go to www.statecraft.pub. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.statecraft.pub

Today, we’re joined by Bobby Fijan. He’s a co-founder of the American Housing Corporation, a startup building housing for families in cities. A burning question motivates his work: How do you make cities places where families can live and thrive? He has a new report out with the Institute of Family Studies looking at what families really want from their apartments.This is a pretty self-indulgent episode for me. I live in Brooklyn with my wife and two-year-old, and we’re expecting our second kid. We want to stay in the city — it’s where our life and community are, and where we’ve put down roots. But the classic route for people like us is to move out to the suburbs once the family grows. I hoped talking to Bobby would help me avoid that fate.Bobby argues that the best ideas for family-friendly housing aren’t new. Pre-war apartments in American cities look a lot like what he’s advocating for. We’ve done this before, and we could do it again.We discuss:* How the financial crisis fuelled a boom in studio apartments* Why did apartments get so much smaller after 2008?* Why are most two-bedroom apartments designed for roommates?* What do families actually want in a floor plan, and why don’t developers build it?* Whether upzoning can helpThanks to Harry Fletcher-Wood and Katerina Barton for their judicious transcript and audio edits.The full transcript to this conversation and many others is available at www.statecraft.pub. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.statecraft.pub

Today, I’m joined by Anup Malani. He’s a professor of law at the University of Chicago, currently on leave, serving as the first Chief Economist at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. This means he oversees economic analysis for the agency managing $2 trillion in annual healthcare spending — 23% of the entire federal budget. CMS runs Medicare for 70 million elderly Americans, Medicaid for low-income families, and the health insurance exchanges where millions buy coverage.Malani answers a lot of questions I have about American healthcare policy:* The US spends 20% of GDP on healthcare. Why is our life expectancy so bad?* How do you crack down on Medicare fraud without hurting patients who need care?* What incentives do private insurers like UnitedHealth have to make patients look sicker than they are?* What do academic economists get wrong about policy?The full transcript for this conversation is at www.statecraft.pub. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.statecraft.pub

This episode was originally recorded on September 4th at the Abundance Conference in DC."Zach Liscow, my guest today, is a professor of law at Yale Law School. In 2022-2023, he was the Chief Economist at the Office of Management and Budget. He's also now my colleague at IFP, as a non-resident senior fellow.I have a bit of a problem today, which is that while Zach may not be a national household name, he might as well be in this audience. As most of you are aware, Zach has worked on many interesting economic topics, but especially on infrastructure costs: why it costs so much to build in the US, what the inputs are, and cross-cutting comparisons.The challenge for me today as an interviewer is that, in part because of Zach’s work, everyone here now knows that infrastructure in the US costs a huge amount to build. I recently reviewed some submissions for a project on transit at IFP, and every other submission referenced the fact that the cost per mile to build a subway in New York is something like eight times more than the equivalent project in Paris.These stylized facts are now embedded in our discourse. And my problem is that this makes it a little hard to figure out how to have a conversation that isn't just all of us nodding in agreement. I'm going to try to tackle that problem, but I just want to lay my cards on the table. This is my fear, and we’ll try to avoid it."The full transcript for this conversation and many others is at www.statecraft.pub. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.statecraft.pub

The full transcript for this conversation is at www.statecraft.pub. When I started this podcast a couple years ago, the idea was more constrained than it is today. We wanted to do exit interviews with civil servants, who were newly free to speak about their experiences and their learnings. The project has expanded: we talk to political scientists, economists, DC wonks, elected officials and people currently in government. But the core value of this project is in that original idea of getting a hold of people as they're leaving the government, pinning them to the wall, and making them reveal their secrets.Today's guest is in that mold. His name is Dean Ball. If you follow AI policy, you already know who he is. Until a couple of weeks ago, Dean was a senior policy advisor for artificial intelligence and emerging technology at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP).Dean and I go back a little while. Most notably, we’ve serve together on one of the most dominant trivia teams DC has seen. But that's not why Dean's important. Dean's had a whirlwind tour over the past few months in the federal government. During that time, he was the organizing author of the Administration's AI Action Plan, a comprehensive roadmap from the White House on federal AI policy.Today, we caught up to talk about that Action Plan, what it takes to write a strategy document for the federal government, and the challenges of implementing that strategy in the face of political, personal, and bureaucratic opposition.I've said in the past that Dean thinks more clearly about the near-term future than most people. I still think that's true, though I don't agree with him on everything here. He's an incredibly sharp thinker and I benefit from talking to him.We discuss:* How to gain influence in the White House* Navigating the interagency process efficiently* Whether the deep state is real* The AI Action Plan* How to implement change across the federal government* The complexities of export controls on AI Chips* Why Dean left the White House after six monthsThanks to Harry Fletcher-Wood for his transcript edits, and to Katerina Barton for her audio edits. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.statecraft.pub

Today I'm talking to Dan Wang. He has a great new book, Breakneck: China's Quest to Engineer the Future. Dan spent the better part of the last decade in China and published a yearly letter summarizing his thoughts, explorations, and eating.Breakneck is like those letters: it goes all over the place, as does our conversation. Topics include:* America's overabundance of lawyers* Whether our ruling class should be all economists* Stylish propaganda* The book collections of Yale professors* iPhone manufacturing* Forced sterilization* Planting cassavaOne of the things I like most about Dan's work is that he's comfortable looking at China through multiple, very different lenses. Parts of Breakneck explicitly use China as a lens to think about the US and its political culture and institutions. Other parts of the book try very hard to take China on its own terms, without reading our own culture into it. It’s that mix that made the book so enjoyable for me, and I hope you enjoy it too.Thank you to Harry Fletcher-Wood for his judicious transcript edits, and to Katerina Barton for her audio edits. You can find the full, annotated transcript to this conversation at www.statecraft.pub. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.statecraft.pub

Today I'm talking to economic historian Judge Glock, Director of Research at the Manhattan Institute. Judge works on a lot of topics: if you enjoy this episode, I'd encourage you to read some of his work on housing markets and the Environmental Protection Agency. But I cornered him today to talk about civil service reform.Since the 1990s, over 20 red and blue states have made radical changes to how they hire and fire government employees — changes that would be completely outside the Overton window at the federal level. A paper by Judge and Renu Mukherjee lists four reforms made by states like Texas, Florida, and Georgia: * At-will employment for state workers* The elimination of collective bargaining agreements* Giving managers much more discretion to hire* Giving managers much more discretion in how they pay employeesJudge finds decent evidence that the reforms have improved the effectiveness of state governments, and little evidence of the politicization that federal reformers fear. Meanwhile, in Washington, managers can’t see applicants’ resumes, keyword searches determine who gets hired, and firing a bad performer can take years. But almost none of these ideas are on the table in Washington.Thanks to Harry Fletcher-Wood for his judicious transcript edits and fact-checking, and to Katerina Barton for audio edits.Judge, you have a paper out about lessons for civil service reform from the states. Since the ‘90s, red and blue states have made big changes to how they hire and fire people. Walk through those changes for me.I was born and grew up in Washington DC, heard a lot about civil service throughout my childhood, and began to research it as an adult. But I knew almost nothing about the state civil service systems. When I began working in the states — mainly across the Sunbelt, including in Texas, Kansas, Arizona — I was surprised to learn that their civil service systems were reformed to an absolutely radical extent relative to anything proposed at the federal level, let alone implemented.Starting in the 1990s, several states went to complete at-will employment. That means there were no official civil service protections for any state employees. Some managers were authorized to hire people off the street, just like you could in the private sector. A manager meets someone in a coffee shop, they say, "I'm looking for exactly your role. Why don't you come on board?" At the federal level, with its stultified hiring process, it seemed absurd to even suggest something like that.You had states that got rid of any collective bargaining agreements with their public employee unions. You also had states that did a lot more broadbanding [creating wider pay bands] for employee pay: a lot more discretion for managers to reward or penalize their employees depending on their performance.These major reforms in these states were, from the perspective of DC, incredibly radical. Literally nobody at the federal level proposes anything approximating what has been in place for decades in the states. That should be more commonly known, and should infiltrate the debate on civil service reform in DC.Even though the evidence is not absolutely airtight, on the whole these reforms have been positive. A lot of the evidence is surveys asking managers and operators in these states how they think it works. They've generally been positive. We know these states operate pretty well: Places like Texas, Florida, and Arizona rank well on state capacity metrics in terms of cost of government, time for permitting, and other issues.Finally, to me the most surprising thing is the dog that didn't bark. The argument in the federal government against civil service reform is, “If you do this, we will open up the gates of hell and return to the 19th-century patronage system, where spoilsmen come and go depending on elected officials, and the government is overrun with political appointees who don't care about the civil service.” That has simply not happened. We have very few reports of any concrete examples of politicization at the state level. In surveys, state employees and managers can almost never remember any example of political preferences influencing hiring or firing.One of the surveys you cited asked, “Can you think of a time someone said that they thought that the political preferences were a factor in civil service hiring?” and it was something like 5%.It was in that 5-10% range. I don't think you'd find a dissimilar number of people who would say that even in an official civil service system. Politics is not completely excluded even from a formal civil service system.A few weeks ago, you and I talked to our mutual friend, Don Moynihan, who's a scholar of public administration. He's more skeptical about the evidence that civil service reform would be positive at the federal level.One of your points is, “We don't have strong negative evidence from the states. Productivity didn’t crater in states that moved to an at-will employment system.” We do have strong evidence that collective bargaining in the public sector is bad for productivity.What I think you and Don would agree on is that we could use more evidence on the hiring and firing side than the surveys that we have. Is that a fair assessment?Yes, I think that's correct. As you mentioned, the evidence on collective bargaining is pretty close to universal: it raises costs, reduces the efficiency of government, and has few to no positive upsides.On hiring and firing, I mentioned a few studies. There's a 2013 study that looks at HR managers in six states and finds very little evidence of politicization, and managers generally prefer the new system. There was a dissertation that surveyed several employees and managers in civil service reform and non-reform states. Across the board, the at-will employment states said they had better hiring retention, productivity, and so forth. And there's a 2002 study that looked specifically at Texas, Florida, and Georgia after their reforms, and found almost universal approbation inside the civil service itself for these reforms.These are not randomized control trials. But I think that generally positive evidence should point us directionally where we should go on civil service reform. If we loosen restrictions on discipline and firing, decentralize hiring and so forth — we probably get some productivity benefits from it. We can also know, with some amount of confidence, that the sky is not going to fall, which I think is a very important baseline assumption. The civil service system will continue on and probably be fairly close to what it is today, in terms of its political influence, if you have decentralized hiring and at-will employment.As you point out, a lot of these reforms that have happened in 20-odd states since the ‘90s would be totally outside the Overton window at the federal level. Why is it so easy for Georgia to make a bipartisan move in the ‘90s to at-will employment, when you couldn't raise the topic at the federal level?It's a good question. I think in the 1990s, a lot of people thought a combination of the 1978 Civil Service Reform Act — which was the Carter-era act that somewhat attempted to do what these states hoped to do in the 1990s — and the Clinton-era Reinventing Government Initiative, would accomplish the same ends. That didn't happen.That was an era when civil service reform was much more bipartisan. In Georgia, it was a Democratic governor, Zell Miller, who pushed it. In a lot of these other states, they got buy-in from both sides. The recent era of state reform took place after the 2010 Republican wave in the states. Since that wave, the reform impetus for civil service has been much more Republican. That has meant it's been a lot harder to get buy-in from both sides at the federal level, which will be necessary to overcome a filibuster.I think people know it has to be very bipartisan. We're just past the point, at least at the moment, where it can be bipartisan at the federal level. But there are areas where there's a fair amount of overlap between the two sides on what needs to happen, at least in the upper reaches of the civil service.It was interesting to me just how bipartisan civil service reform has been at various times. You talked about the Civil Service Reform Act, which passed Congress in 1978. President Carter tells Congress that the civil service system:“Has become a bureaucratic maze which neglects merit, tolerates poor performance, permits abuse of legitimate employee rights, and mires every personnel action in red tape, delay, and confusion.”That's a Democratic president saying that. It’s striking to me that the civil service was not the polarized topic that it is today.Absolutely. Carter was a big civil service reformer in Georgia before those even larger 1990s reforms. He campaigned on civil service reform and thought it was essential to the success of his presidency. But I think you are seeing little sprouts of potential bipartisanship today, like the Chance to Compete Act at the end of 2024, and some of the reforms Obama did to the hiring process. There's options for bipartisanship at the federal level, even if it can’t approach what the states have done.I want to walk through the federal hiring process. Let's say you're looking to hire in some federal agency — you pick the agency — and I graduated college recently, and I want to go into the civil service. Tell me about trying to hire somebody like me. What's your first step?It's interesting you bring up the college graduate, because that is one recent reform: President Trump put out an executive order trying to counsel agencies to remove the college degree requirement for job postings. This happened in a lot of states first, like Maryland, and that's also been bipartisan. This requirement for a college degree — which was used as a very unfortunate proxy for ability at a lot of these jobs — is now being removed. It's not across the whole federal government

Today we're joined by Dr. Rob Johnston. He's an anthropologist, an intelligence community veteran, and author of the cult classic Analytic Culture in the US Intelligence Community, a book so influential that it's required reading at DARPA. But first and foremost, Johnston is an ethnographer. His focus in that book is on how analysts actually produce intelligence analysis.Johnston answers a lot of questions I've had for a while about intelligence and spying, such as:* Why do we seem to get big predictions wrong so consistently?* Why can't the CIA find analysts who speak the language of the country they're analyzing?* Why do we prioritize expensive satellites over human intelligence?We also discuss a meta-question I always come back to on Statecraft: is being good at this stuff an art or a science? By “this stuff,” I’m referring to intelligence analysis, but I think that the question generalizes across policymaking. Would more formalizing and systematizing make our spies, diplomats, and EPA bureaucrats better? Or would it lead to more bureaucracy, more paper, and worse outcomes? How do you build processes in the government that actually make you better at your job?You can find the full transcript for this conversation at www.statecraft.pub. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.statecraft.pub

We’ve covered the US Agency for International Development, or USAID, pretty consistently on Statecraft, since our first interview on PEPFAR, the flagship anti-AIDS program, in 2023. When DOGE came to USAID, I was extremely critical of the cuts to lifesaving aid, and the abrupt, pointlessly harmful ways in which they were enacted. In March, I wrote, “The DOGE team has axed the most effective and efficient programs at USAID, and forced out the chief economist, who was brought in to oversee a more aggressive push toward efficiency.”Today, we’re talking to that forced-out chief economist, Dean Karlan. Dean spent two and a half years at the helm of the first-ever Office of the Chief Economist at USAID. In that role, he tried to help USAID get better value from its foreign aid spending. His office shifted $1.7 billion of spending towards programs with stronger evidence of effectiveness. He explains how he achieved this, building a start-up within a massive bureaucracy. I should note that Dean is one of the titans of development economics, leading some of the most important initiatives in the field (I won’t list them, but see here for details), and I think there’s a plausible case he deserves a Nobel.Throughout this conversation, Dean makes a point much better than I could: the status quo at USAID needed a lot of improvement. The same political mechanisms that get foreign aid funded by Congress also created major vulnerabilities for foreign aid, vulnerabilities that DOGE seized on. Dean believes foreign aid is hugely valuable, a good thing for us to spend our time, money, and resources on. But there's a lot USAID could do differently to make its marginal dollar spent more efficient.DOGE could have made USAID much more accountable and efficient by listening to people like Dean, and reformers of foreign aid should think carefully about Dean’s criticisms of USAID, and his points for how to make foreign aid not just resilient but politically popular in the long term.We discuss* What does the Chief Economist do?* Why does 170% percent of USAID funds come already earmarked by Congress?* Why is evaluating program effectiveness institutionally difficult?* Why don’t we just do cash transfers for everything?* Why institutions like USAID have trouble prioritizing* Should USAID get rid of gender/environment/fairness in procurement rules?* Did it rely too much on a small group of contractors?* What’s changed in development economics over the last 20 years?* Should USAID spend more on governance and less on other forms of aid? * How DOGE killed USAID — and how to bring it back better* Is depoliticizing foreign aid even possible?* Did USAID build “soft power” for the United States?This is a long conversation: you can jump to a specific section with the index above. If you just want to hear about Dean’s experience with DOGE, you can click here or go to the 45-minute mark in the audio. And if you want my abbreviated summary of the conversation, see these two Twitter threads. But I think the full conversation is enlightening, especially if you want to understand the American foreign aid system. Thanks to Harry Fletcher-Wood for his judicious edits.Our past coverage of USAIDDean, I'm curious about the limits of your authority. What can the Chief Economist of USAID do? What can they make people do?There had never been an Office of the Chief Economist before. In a sense, I was running a startup, within a 13,000-employee agency that had fairly baked-in, decentralized processes for doing things.Congress would say, "This is how much to spend on this sector and these countries." What you actually fund was decided by missions in the individual countries. It was exciting to have that purview across the world and across many areas, not just economic development, but also education, social protection, agriculture. But the reality is, we were running a consulting unit within USAID, trying to advise others on how to use evidence more effectively in order to maximize impact for every dollar spent.We were able to make some institutional changes, focused on basically a two-pronged strategy. One, what are the institutional enablers — the rules and the processes for how things get done — that are changeable? And two, let's get our hands dirty working with the budget holders who say, "I would love to use the evidence that's out there, please help guide us to be more effective with what we're doing."There were a lot of willing and eager people within USAID. We did not lack support to make that happen. We never would've achieved anything, had there not been an eager workforce who heard our mission and knocked on our door to say, "Please come help us do that."What do you mean when you say USAID has decentralized processes for doing things?Earmarks and directives come down from Congress. [Some are] about sector: $1 billion dollars to spend on primary school education to improve children's learning outcomes, for instance. The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) [See our interview with former PEPFAR lead Mark Dybul] is one of the biggest earmarks to spend money specifically on specific diseases. Then there's directives that come down about how to allocate across countries.Those are two conversations I have very little engagement on, because some of that comes from Congress. It’s a very complicated, intertwined set of constraints that are then adhered to and allocated to the different countries. Then what ends up happening is — this is the decentralized part — you might be a Foreign Service Officer (FSO) working in a country, your focus is education, and you’re given a budget for that year from the earmark for education and told, "Go spend $80 million on a new award in education." You’re working to figure out, “How should we spend that?” There might be some technical support from headquarters, but ultimately, you're responsible for making those decisions. Part of our role was to help guide those FSOs towards programs that had more evidence of effectiveness.Could you talk more about these earmarks? There's a popular perception that USAID decides what it wants to fund. But these big categories of humanitarian aid, or health, or governance, are all decided in Congress. Often it's specific congressmen or congresswomen who really want particular pet projects to be funded.That's right. And the number that I heard is that something in the ballpark of 150-170% of USAID funds were earmarked. That might sound horrible, but it's not.How is that possible?Congress double-dips, in a sense: we have two different demands. You must spend money on these two things. If the same dollar can satisfy both, that was completely legitimate. There was no hiding of that fact. It's all public record, and it all comes from congressional acts that create these earmarks. There's nothing hidden underneath the hood.Will you give me examples of double earmarking in practice? What kinds of goals could you satisfy with the same dollar?There’s an earmark for Development Innovation Ventures (DIV) to do research, and an earmark for education. If DIV is going to fund an evaluation of something in the education space, there's a possibility that that can satisfy a dual earmark requirement. That's the kind of thing that would happen. One is an earmark for a process: “Do really careful, rigorous evaluations of interventions, so that we learn more about what works and what doesn't." And another is, "Here's money that has to be spent on education." That would be an example of a double dip on an earmark.And within those categories, the job of Chief Economist was to help USAID optimize the funding? If you're spending $2 billion on education, “Let's be as effective with that money as possible.”That's exactly right. We had two teams, Evidence Use and Evidence Generation. It was exactly what it sounds like. If there was an earmark for $1 billion dollars on education, the Evidence Use team worked to do systematic analysis: “What is the best evidence out there for what works for education for primary school learning outcomes?” Then, “How can we map that evidence to the kinds of things that USAID funds? What are the kinds of questions that need to be figured out?”It’s not a cookie-cutter answer. A systematic review doesn’t say, "Here's the intervention. Now just roll it out everywhere." We had to work with the missions — with people who know the local area — to understand, “What is the local context? How do you appropriately adapt this program in a procurement and contextualize it to that country, so that you can hire people to use that evidence?”Our Evidence Generation team was trying to identify knowledge gaps where the agency could lead in producing more knowledge about what works and what doesn't. If there was something innovative that USAID was funding, we were huge advocates of, "Great, let's contribute to the global public good of knowledge, so that we can learn more in the future about what to do, and so others can learn from us. So let's do good, careful evaluations."Being able to demonstrate what good came of an intervention also serves the purpose of accountability. But I've never been a fan of doing really rigorous evaluations just for the sake of accountability. It could discourage innovation and risk-taking, because if you fail, you'd be seen as a failure, rather than as a win for learning that an idea people thought was reasonable didn't turn out to work. It also probably leads to overspending on research, rather than doing programs. If you're doing something just for accountability purposes, you're better off with audits. "Did you actually deliver the program that you said you would deliver, or not?"Awards over $100 million dollars did go through the front office of USAID for approval. We added a process — it was actually a revamped old process — where they stopped off in my office. We were able to provide guidance on the cost-effectiveness of proposals that would then be factored

At the end of April, the Transit Costs Project released a report: it’s called How to Build High-Speed Rail on the Northeast Corridor. As the name suggests, the authors of the report had a simple goal: the stretch of the US from DC and Baltimore through Philadelphia to New York and up to Boston, the densest stretch of the country. It’s an ideal location for high-speed rail. How could you actually build it — trains that get you from DC to NYC in two hours, or NYC to Boston in two hours — without breaking the bank?That last part is pretty important. The authors think you could do it for under $20 billion dollars. That’s a lot of money, but it’s about five times less than the budget Amtrak says it would require. What’s the difference? How is it that when Amtrak gets asked to price out high-speed rail, it gives a quote that much higher?We brought in Alon Levy, transit guru and the lead author of the report, to answer the question, and to explain a bunch of transit facts to a layman like me. Is this project actually technically feasible? And, if it is, could it actually work politically?* How to cut time off the Northeast Corridor* Operations coordination as a time-saver* The move away from the Mad Men commuter* Was our episode on the Green Line extension wrong?The full transcript for this conversation is at www.statecraft.pub. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.statecraft.pub

Happy Fourth of July! I’m attending a wedding today, so this episode is from the vault, in a way, although it’s its first time on Statecraft. I originally published this essay in January of 2022 on Mirror, shortly after my wife had joined the core team of a DAO that was attempting to acquire a first-edition copy of the US Constitution. I had been reading a history of the constitutional convention, and it seemed fitting to write about it on a thematic site. Yes, July 4th is about the Declaration of Independence, not the Constitution. Cut me some slack, please!You can find the transcript for this episode and many others at www.statecraft.pub. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.statecraft.pub

The decisions that humans make can be extraordinarily costly. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were multi-trillion-dollar decisions. If you can improve the accuracy of forecasting individual strategies by just a percentage point, that would be worth tens of billions of dollars. Yet society does not invest tens of billions of dollars in figuring out how to improve the accuracy of human judgment. That seems really odd.That’s a quote from today’s interviewee, who has made his career helping the intelligence community predict the future better. In this interview, we discuss:* Which prediction methods perform the best?* How does IARPA create tech for American spies?* What technologies give democracies an advantage over autocracies?* Could the Internet have been designed better?Our interviewee, Jason Matheny, championed research into human judgment and forecasting at the R&D lab for the intelligence community: the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity, or IARPA, which he directed from 2015-2018.[This interview was originally published in 2023, at this link, without the audio: Statecraft was still transcript-only then.]You can find the transcript for this conversation at www.statecraft.pub. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.statecraft.pub

There are many forces in policymaking (and in our lives generally) that push us towards the short term. Many of the most important measurements in political life are on extremely tight timelines: election cycles, monthly unemployment reports, even the President's daily intelligence briefing. The pressure to get results — and to show results — on a tight turnaround is incredible.One of my questions on Statecraft for a while has been: How do you build a machine to get long-term results? Whether it's a new agency or a new initiative, how do you set up a structure to work toward a goal that's 10, or 20, or 50 years away? And how do you protect that structure from short-term political pressures?Today's interviewee is Sir Rory Collins. Sir Rory has spent a full 20 years building and leading one of the most important scientific resources in the world: the UK Biobank.The Biobank represents a fascinating case study in long-term thinking. It's a database of half a million British participants whose health is being tracked longitudinally for the next 30 years. The Biobank was established with the knowledge that the upfront work, and the spending required, would only really start to pay off 15 years later. When Sir Rory went in for the 10-year review with funders, they asked what had been achieved so far. He said, “Nothing.”But today, UK Biobank is paying massive dividends: It's democratized access to population-scale data for researchers worldwide, and it's already yielding amazing insights into the causes of and cures for disease. I wanted to understand how he built the UK Biobank, and, just as importantly, how he managed to sustain it over a long period of time.We discussed* How to create long-term value in research* How to recruit half a million research subjects* Why the Biobank deferred so many decisions* How other countries’ prospective studies are learning from the UK BiobankThe transcript for this conversation and many others is at www.statecraft.pub. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.statecraft.pub