Discover Justified Posteriors

Justified Posteriors

Justified Posteriors

Author: Seth Benzell and Andrey Fradkin

Subscribed: 13Played: 327Subscribe

Share

© Andrey Fradkin

Description

Explorations into the economics of AI and innovation. Seth Benzell and Andrey Fradkin discuss academic papers and essays at the intersection of economics and technology.

empiricrafting.substack.com

empiricrafting.substack.com

28 Episodes

Reverse

In this episode, we sit down with Ben Golub, economist at Northwestern University, to talk about what happens when AI meets academic research, social learning, and network theory.We start with Ben’s startup Refine, an AI-powered technical referee for academic papers. From there, the conversation ranges widely: how scholars should think about tooling, why “slop” is now cheap, how eigenvalues explain viral growth, and what large language models might do to collective belief formation. We get math, economics, startups, misinformation, and even cow tipping.Links & References* Refine — AI referee for academic papers* Harmonic — Formal verification and proof tooling for mathematics* Matthew O. Jackson — Stanford economist and leading scholar of networks and social learning* Cow tipping (myth) — Why you can’t actually tip a cow (physics + folklore)* The Hype Machine — Sinan Aral on how social platforms amplify misinformation* Sequential learning / information cascades / DeGroot Model* AI Village — Multi-agent AI simulations and emergent behavior experiments* Virtual currencies & Quora credits — Internal markets for attention and incentivesTranscript:Seth: Welcome to Justified Posteriors, the podcast that updates its beliefs about the economics of AI and technology.Seth: I’m Seth Benzel, hoping my posteriors are half as good as the average of my erudite Friends is coming to you from Chapman University in sunny Southern California.Andrey: And I’m Andrey Fradkin coming to you from San Francisco, California, and I’m very excited that our guest for today is Ben Goleb, who is a prominent economist at Northwestern University. Ben has won the Calvó-Armengol International Prize, which recognizes a top researcher in economics or social science, younger than 40 years old, for contributions to theory and comprehension of mechanisms of social interaction.Andrey: So you want someone to analyze your social interactions, Ben is definitely the guy.Seth: If it’s in the network,Andrey: Yeah, he is, he was also a member of the Harvard Society of Fellows and had a brief stint working as an intern at Quora, and we’ve known each other for a long time. So welcome to the show, Ben.Ben: Thank you, Andrey. Thank you, Seth. It’s wonderful to be on your podcast.Refine: AI-Powered Paper ReviewingAndrey: All right. Let’s get started. I want us to get started on what’s very likely been the most on your mind thing, Ben, which is your new endeavor, Refine.Ink. Why don’t you tell us a little bit about, give us the three minute spiel about what you’re doing.Seth: and tell us why you didn’t name your tech startup after a Lord of the Rings character.Ben: Man, that’s a curve ball right there. All right, I’ll tell you what, I’ll put that on background processing. So, what refine is, is it’s an AI referee technical referee. From a user perspective, what happens is you just give it a paper and you get the experience of a really obsessive research assistant reading for as long as it takes to get through the whole thing, probing it from every angle, asking every lawyerly question about whether things make sense.Ben: And then that feedback, hopefully the really valuable parts that an author would wanna know are distilled and delivered. So as my co-founder Yann Calvó López puts it, obsession is really the obsessiveness is the nature of the company. We just bottled it up and we give it to people. So that’s the basic product—it’s an AI tool. It uses AI obviously to do all of this thinking. One thing I’ll say about it is that I have long felt it was a scandal that the level of tooling for scholars is a tiny fraction of what it is for software engineers.Ben: And obviously software engineering is a much larger and more economically valuableSeth: Boo.Ben: leastAndrey: Oh, disagree.Ben: In certain immediate quantifications. But I felt that ever since I’ve been using tech, I just felt imagine if we had really good tools and then there was this perfect storm where my co-founder and I felt we could make a tool that was state of the art for now. So that’s how I think of it.Seth: I have to quibble with you a little bit about the user experience because the way I went, the step zero was first, jaw drops to the floor at the sticker price. How much do you,Ben: not,Seth: But then I will say I have used it myself and on a paper I recently submitted, it really did find a technical error and I would a kind of error that you wouldn’t find, just throwing this into ChatGPT as of a few months ago. Who knows with the latest Gemini. But it really impressed me with my limited time using it.Andrey: So.Ben: is probably, if you think about the sticker price, if you compare that to the amount of time you’d have, you’d have had to pay error.Seth: Yeah. And water. If I didn’t have water, I’d die, so I should pay a million for water.Andrey: A question I had: how do you know it’s good? Isn’t this whole evals thing very tricky?Seth: Hmm.Andrey: Is there Is there, a paper review or benchmark that you’ve come across, or did you develop your own?Ben: Yeah. That’s a wonderful question. As Andrey knows, he’s a super insightful person about AI and this goes to the core of the issue because all the engineers we work with are immediately like, okay, I get what you’re doing.Ben: Give me the evals, give me the standard of quality. So we know we’re objectively doing a good job. What we have are a set of papers where we know what ground truth is. We basically know everything that’s wrong with them and every model update we run, so that’s a small set of fairly manual evaluations that’s available. I think one of the things that users experience is they know their own papers well and can see over time that sometimes we find issues that they know about and then sometimes we find other issues and we can see whether they’re correct.Ben: We’re not at the point where we can make confident precision recall type assessments. But another thing that we do, which I find cool, was whenever tools that our competitors come out, like Andrew Ng put out a cool paper reviewer thing targeted at CS conferences.Ben: And what we do is we just run that thing, we run our thing, we put both of them into Gemini 2.0, and we say, could you please assess these side by side as reviews of the same paper? Which one caught mistakes? We try to make it a very neutral prompt, and that’s an eval that is easy to carry out.Ben: But actually we’re in the market. We’d love to work with people who are excited about doing this for refine. We finally have the resources to take a serious run at it as founders. The simple truth is because my co-founder and I are researchers as well as founders, we constantly look at how it’s doing on documents we know.Ben: And it’s a very seat of the pants thing for now, to tell the truth.Andrey: Do you think that there’s an aspect of data-driven here and that one of your friends puts their paper into it and says, well, you didn’t catch this mistake, or you didn’t catch that mistake, and then you optimize towards that. Is that a big part of your development process?Ben: Yeah, it was more. I think we’ve reached an equilibrium where of the feedback of that form we hear, there’s usually a cost to catching it. But early on that was basically, I would just tell everyone I could find, and there were a few. When I finally had the courage to tell my main academic group chat about it and I gave it, immediately people had very clear feedback and this was in the deep, I think the first reasoning model we used for the substantive feedback was DeepSeek R1 and people, we immediately felt, okay, this is 90% slop.Ben: And that’s where we started by iterating. We got to where, and one great thing about having academic friends is they’re not gonna be shy to tell you that your thought of paper.Refereeing Math and AI for Economic TheoryAndrey: One thing that we wanted to dig a little bit into is how you think about refereeing math andSeth: Mm-hmm.Andrey: More generally opening it up to how are economic theorists using AI for math?Ben: So say a little more about your question. When you say mathSeth: Well, we see people, Axiom, I think is the name of the company, immediately converting these written proofs into Lean. Is that the end game for your tool?Ben: I see, yes. So good. Our vision for the company is that, at least for quite a while, I think there’s gonna be this product layer between tools, the core AI models and the things that are necessary to bring your median, ambitiousSeth: MiddleBen: notSeth: theorists, that’s what we call ourselves.Ben: Well, yeah. Or middle, but in a technical dimension, I think it’s almost certainly true that the median economist doesn’t use GitHub almost ever. If you told them, they set up something that, a tool that works through the terminal, think about Harmonic, right?Ben: Their tools are all, they say the first step is, go grab this from a repository and run these command line things to, they try to make it pretty easy, but it’s still a terminal tool. So a big picture vision is that we think the most sophisticated tools will be, there will be a lot of them that are not yet productized and we can just make the bundle for scholars to actually use it in their work.Ben: Now about the question of formalization per se, I have always been excited to use formalization in particular to make that product experience happen. For formalized math, my understanding is right now the coverage of the auto formalization systems is very jagged across, even across. If you compare number theory to algebraic geometry, the former is in good shape for people to start solving Erdős problems or combinatorial number theory, things like that, people can just start doing that. For algebraic geometry, there are a lot of basics that aren’t built out and so all of the lean proofs will contain a lot of stories that the user has to say, am I fine considering that settled or not?Ben: And that’s not really an experience that makes sense fo

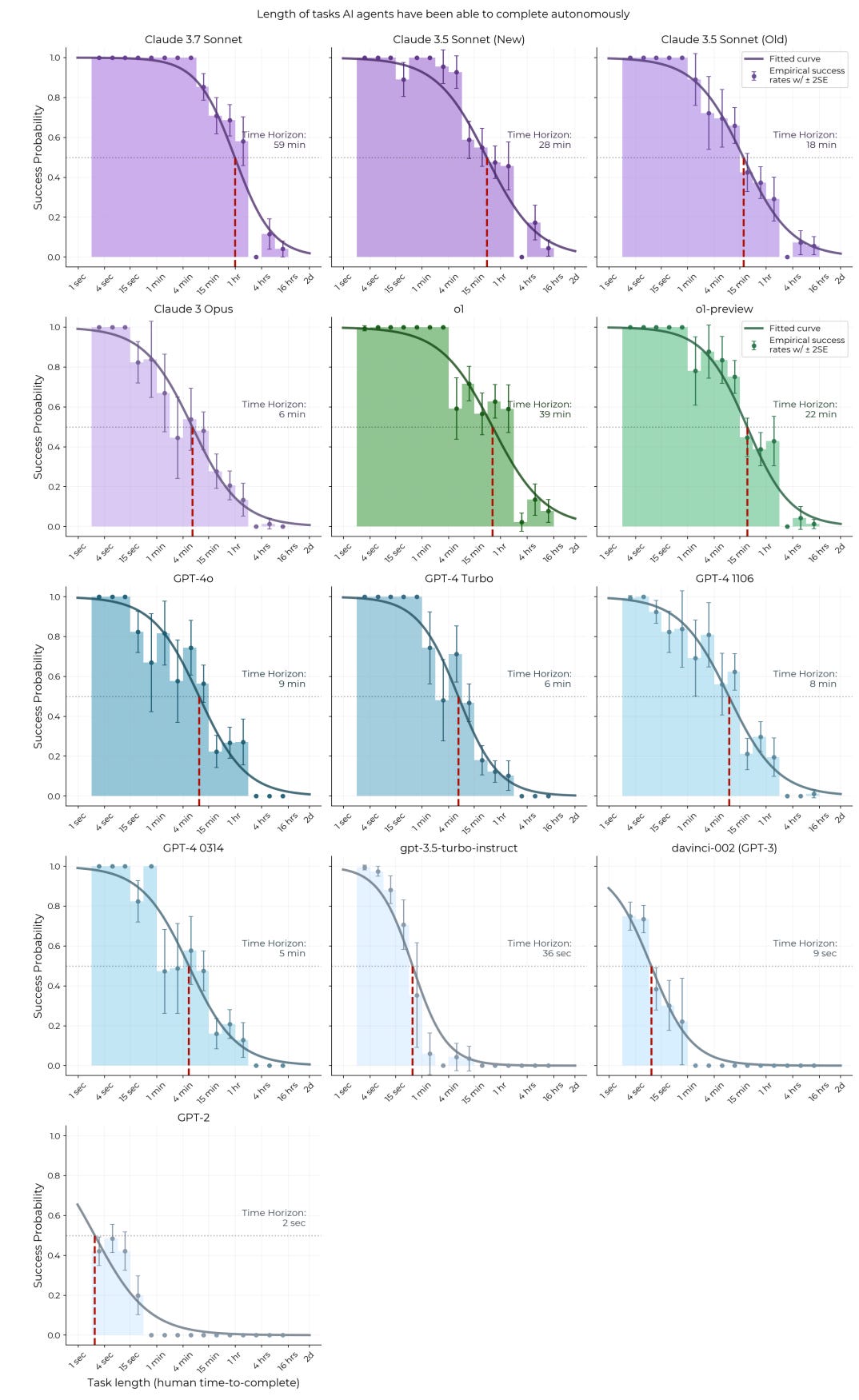

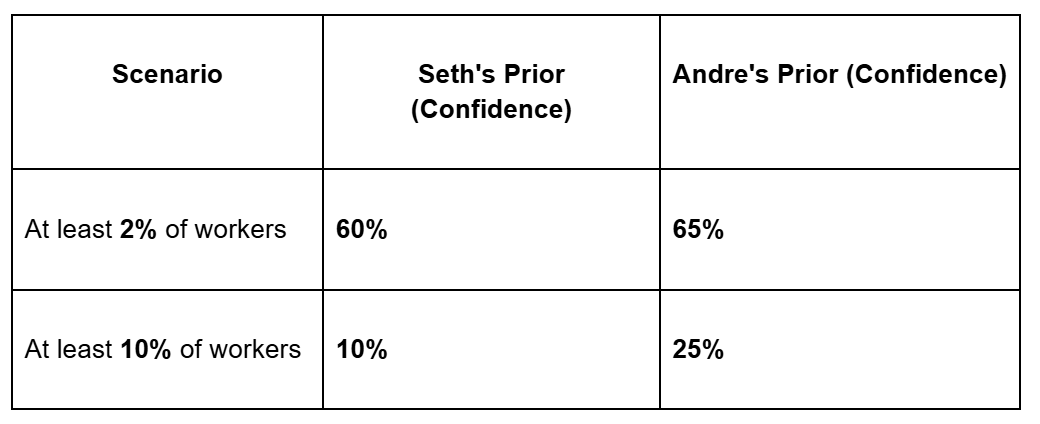

Seth and Andrey are back to evaluating an AI evaluation, this time discussing METR’s paper “Measuring AI Ability to Complete Long Tasks.” The paper’s central claim is that the “effective horizon” of AI agents—the length of tasks they can complete autonomously—is doubling every 7 months. Extrapolate that, and AI handles month-long projects by decade’s end. They discuss the data and the assumptions that go into this benchmark. Seth and Andrey start by walking through the tests of task length, from simple atomic actions to the 8-hour research simulations in RE-Bench. They discuss whether the paper properly measures task length median success with their logarithmic models. And, of course, they zoom out to ask whether “time” is even the right metric for AI capability, and whether METR applies the concept correctly.Our hosts also point out other limitations and open questions the eval leaves us with. Does the paper properly acknowledge how messy long tasks get in practice? AI still struggles with things like playing Pokémon or coordinating in AI Village—tasks that are hard to decompose cleanly. Can completing one 10-hour task really be equated with reliably completing ten 1-hour subtasks? And Seth has a bone to pick about a very important study detail omitted from the introduction. The Priors that We Update On Are:* Is evaluating AI by time (task length) more useful/robust than evaluating by economic value (as seen in OpenAI’s GDP-eval)?* How long until an AI can autonomously complete a “human-month” sized task (defined here as a solid second draft of an economics paper, given data and research question)?* Seth’s Prior: 50/50 in 5 years, >90% in 10 years.* Andrey’s Prior: 50/50 in 5 years, almost certain in 10 years.Listen to see how our perspectives change after reading!Links & Mentions:* The Paper: Measuring AI Ability to Complete Long Tasks by METR* Complementary Benchmarks:* RE-Bench (Research Engineering Benchmark) - METR’s eval for AI R&D capabilities.* H-CAST (Human-Calibrated Autonomy Software Tasks) - The benchmark of 189 tasks used in the study.* The “Other” Eval: GDP-eval: Evaluating AI Model Performance on Real-World Economically Valuable Tasks by OpenAI* AI 2027 (A forecasting scenario discussed)* AI Village - A project where AI agents attempt to coordinate on real-world tasks.* Steve Newman on the “100 Person-Year” Project (Creator of Writely/Google Docs).* In the Beginning... Was the Command Line by Neal Stephenson* Raj ChettyTranscript[00:14] Seth Benzell: Welcome to the Justified Posteriors podcast, the podcast that updates its beliefs about the economics of AI and technology. I’m Seth Benzell, wondering just how long a task developing an AI evaluation is, at Chapman University in sunny Southern California.Andrey Fradkin: And I’m Andrey Fradkin, becoming very sad as the rate of improvement in my ability to do tasks is nowhere near the rate at which AI is improving. Coming to you from San Francisco, California.Andrey: All right, Seth. You mentioned how long it takes to do an eval. I think this is going to be a little bit of a theme of our podcast about how actually, evals are pretty hard and expensive to do. Recently there was a Twitter exchange between one of the METR members talking about their eval, which we’ll be talking about today, where he says that for each new model to evaluate it takes approximately 25 hours of staff time, but maybe even more like 60 hours in rougher cases. And that’s not even counting all the compute that’s required to do these evaluations.So, you know, evals get thrown around. I think people knowing evals know how hard they are, but I think as outsiders, we take them for granted. And we shouldn’t, because it certainly takes a lot of work. But yeah, with that in mind, what do you want to say, Seth?Seth: Well, I guess I want to say that we, I think we are the leaders in changing people’s opinions about the importance of these evals. The public responded very positively to our recent eval of Open AI’s GDP-eval, which was trying to look to bring Daron Acemoglu’s view of how can we evaluate the economic potential economic impact of AI to actual task-by-task-by-task, how successful is this AI system. People loved it. Now you demanded it, we listened. We’re coming back to you to talk to you about a new eval—well not a new eval, it’s about eight months old, but it’s the Godzilla of evals. It’s the Kaiju of evals. It’s this paper called “Measuring AI Ability to Complete Long Tasks,” a study that came out by METR. We’ve seen some updates or new evaluations of models since this first came out in March of 2025. Andrey, do you want to list the authors of this paper?[3:05] Andrey: As usual I don’t. There are a lot of authors of this paper. But, you know, I’ve interacted with some of the authors of this paper, I have a lot of respect for them. I have a lot of respect for the METR organization.Seth: Okay. But at a high level, just in a sentence, what this wants to do is evaluate different frontier AI models by the criteria of: “how long are the tasks that they complete”?” Andrey: I guess what I would say before we get to our priors is, just as context, this, from what everything I’ve seen, is the most influential evaluation of AI progress in the world right now. It is a measure that all important new models are benchmarked against. If something is above the trend, it’s news. If something is below the trend, it’s news. If something’s on the trend, it’s news. And it’s caused a lot of people to change their minds about the likely path of AI progress. So I’m very excited to discuss this.Seth: It’s been the source of many “we’re so back” memes. Yeah, I totally agree Andrey. Am I right that this was a paper that was partly inspiring the AI 2027 scenario by favorite blogger Scott Alexander?Andrey: I don’t know if it inspired it, but I think it was used as part of the evidence in that. Just to be clear though, AI 2027, it’s a scenario that was proposed that seemed a bit too soon of a vision for AGI taking over the world by many folks. We have not done an episode on it.Seth: We haven’t done an episode on it. But it’s fair to say that people look at the results of this paper and they see, you know, they see a trend that they extrapolate. But before we get into the details of the paper, are we ready to get into our priors?Andrey: Let’s do it.[05:50] Seth: Okay, so Andrey, just based on that headline description, that instead of evaluating AI systems by trying to go occupation by occupation and try to find tasks in those occupations that are economically valuable and then trying to see what percentage of those tasks the AI can do—that’s what the Open AI GDPval approach that we recently reviewed did—this approach is trying to evaluate tasks again by how long they are. So comparing those two approaches, I guess my first prior is, before we read this paper, which of those approaches do you see as like kind of intuitively more promising?Andrey: One way of thinking about this is tasks are, or things people do which could be a series of tasks, are bundles and they’re bundles embedded in some higher dimensional space. And what these two evals are doing, this one we’re discussing here versus GDPval, is they’re embedding them into different spaces. One of them is a time metric. And one of them is a dollar metric, right? And you can just by phrasing it that way, you can see what some of the issues might be with either. With the dollar metric, well, what are people getting paid for? Is it a specific deliverable or is it being on call or being the responsible party for something? So you can see how it’s kind of hard to really convert lots of things into dollar values at a systematic level. Now, you can say the same thing about how long it takes to do something. Of course, it takes different people very different times to do different tasks. And then once again chaining tasks together, how to rethink about how long it takes to do that. So I think they’re surprisingly similar. I think maybe this length of time one is more useful at the moment because it seems simpler to do frankly. It seems like, yes we can get an estimate for how long it takes to do something. It’s not going to be perfect, it’s going to be noisy, but we can get it and then we can just see whether the model does it. And that’s easier than trying to translate tasks to dollar values in my opinion.[8:42] Seth: Right. I guess I also am tempted to reject the premise of this question and say that they’re valuable for different things. But I guess I come into this thinking about, you know, we think about AI agents as opposed to AI tools as being this next frontier of automation and potentially supercharging the economy. And it really does feel like the case that working with AI models, the rate limiter is the human. It’s how often the human has to stop and give feedback and say, “Okay, here’s the next step,” or “Hey, back up a little bit and try again.” So going in, I would say I was kind of in equipoise about which of the two is the most useful kind of as a projection for where this is going. Maybe on your side of the ledger saying that economic value is kind of a socioeconomic construct, right? That could definitely change a lot even without the tool changing. Whereas time seems more innately connected to difficulty. You can think about psychometric measures of difficulty where we think about, you know, a harder exam is a longer exam. So at least going in, I think that this has a lot of potential to even potentially surpass GDP-eval in terms of its value for projection.Andrey: Yes. Yeah, yeah. Seth: Okay. The next one I was thinking to ask you Andrey was, if we buy all the premises of whatever context the paper sets up for us, the question I’d like to think about is: how long until AI can do a human month-size task on its own? In the abstract of the paper, we have that happening within five years, by 2030. That seems like a pretty big bite at the app

We continue our conversation with Columbia professor Bo Cowgill. We start with a detour through Roman Jakobson’s six functions of language (plus two bonus functions Seth insists on adding: performative and incantatory). Can LLMs handle the referential? The expressive? The poetic? What about magic?The conversation gets properly technical as we dig into Crawford-Sobel cheap talk models, the collapse of costly signaling, and whether “pay to apply” is the inevitable market response to a world where everyone can produce indistinguishable text. Bo argues we’ll see more referral hiring (your network as the last remaining credible signal), while Andrey is convinced LinkedIn Premium’s limited signals are just the beginning of mechanism design for application markets.We take a detour into Bo’s earlier life running Google’s internal prediction markets (once the largest known corporate prediction market), why companies still don’t use them for decision-making despite strong forecasting performance, and whether AI agents participating in prediction markets will have correlated errors if they all derive from the same foundation models.We then discuss whether AI-generated content will create demand for cryptographic proof of authenticity, whether “proof of humanity” protocols can scale, and whether Bo’s 4-year-old daughter’s exposure to AI-generated squirrel videos constitutes evidence of aggregate information loss.Finally: the superhuman persuasion debate. Andrey clarifies he doesn’t believe in compiler-level brain hacks (sorry, Snow Crash fans), Bo presents survey evidence that 85% of GenAI usage involves content meant for others, and Seth closes with the contrarian hot take that information transmission will actually improve on net. General equilibrium saves us all—assuming a spherical cow.Topics Covered:* Jakobson’s functions of language (all eight of them, apparently)* Signaling theory and the pooling equilibrium problem* Crawford-Sobel cheap talk games and babbling equilibria* “Pay to apply” as incentive-compatible mechanism design* Corporate prediction markets and conflicts of interest* The ABC conjecture and math as a social enterprise* Cryptographic verification and proof of humanity* Why live performance and in-person activities may increase in economic value* The Coasean singularity * Robin Hanson’s “everything is signaling” worldviewPapers & References:* Crawford & Sobel (1982), “Strategic Information Transmission”* Cowgill and Zitzewitz (2015) “Corporate Prediction Markets: Evidence from Google, Ford, and Firm X”.* Jakobson, “Linguistics and Poetics” (1960)* Binet, The Seventh Function of Language* Stephenson, Snow CrashTranscript:Andrey: Well, let’s go to speculation mode.Seth: All right. Speculation mode. I have a proposal that I’m gonna ask you guys to indulge me in as we think about how AI will affect communication in the economy. For my book club, I’ve been recently reading some postmodern fiction. In particular, a book called The Seventh Function of Language.The book is a reference to Jakobson’s six famous functions of language. He is a semioticist who is interested in how language functions in society, and he says language functions in six ways.1 I’m gonna add two bonus ones to that, because of course there are seven functions of language, not just six. Maybe this will be a good framework for us to think about how AI will change different functions of language. All right. Are you ready for me?Bo Cowgill: Yes.Seth: Bo’s ready. Okay.Bo Cowgill: Remember all six when you...Seth: No, we’re gonna do ‘em one by one. Okay. The first is the Referential or Informational function. This is just: is the language conveying facts about the world or not? Object level first. No Straussian stuff. Just very literally telling you a thing.When I think about how LLMs will do at this task, we think that LLMs at least have the potential to be more accurate, right? If we’re thinking about cover letters, the LLMs should maybe do a better job at choosing which facts to describe. Clearly there might be an element of choosing which facts to report as being the most relevant. We can think about, maybe that’s in a different function.If we ask about how LLMs change podcasts? Well, presumably an LLM-based podcast, if the LLM was good enough, would get stuff right more often. I’m sure I make errors. Andrey doesn’t make errors. So restricting attention to this object-level, “is the language conveying the facts it needs to convey,” how do you see LLMs changing communication?Bo Cowgill: Do I go first?Seth: Yeah, of course Bo, you’re the guest.Bo Cowgill: Of course. Sorry, I should’ve known. Well, it sounds like you’re optimistic that it’ll improve. Is that right?Seth: I think that if we’re talking about hallucinations, those will be increasingly fixed and be a non-issue for things like CVs and resumes in the next couple of years. And then it becomes the question of: would an LLM be less able to correctly report on commonly agreed-upon facts than a human? I don’t know. The couple-years-out LLM, you gotta figure, is gonna be pretty good at reliably reproducing facts that are agreed upon.Bo Cowgill: Yeah, I see what you mean. So, I’m gonna say “it depends,” but I’ll tell you exactly what I think it depends on. I think in instances where the sender and the receiver are basically playing a zero-sum game, I don’t think that the LLM is gonna help. And arguably, nothing is gonna help. Maybe costly signaling could help, but...Seth: Sender and the receiver are playing a zero-sum game? If I wanna hire someone, that’s a positive-sum game, I thought.Andrey: Two senders are playing a zero-sum game.Seth: Oh, two senders. Yes. Two senders are zero-sum with each other. Okay.Bo Cowgill: Right. This is another domain-specific answer, but I think that it depends on what game the two parties are playing. Are they trying to coordinate on something? Is it a zero-sum game where they have total opposite objectives? If all costly signaling has been destroyed, then I don’t think that the LLM is gonna help overcome that total separation.On the other hand, if there’s some alignment between sender and receiver—even in a cheap talk world—we know from the Crawford and Sobel literature that you can have communication happen even without the cost of a signal. I do think that in those Crawford and Sobel games, you have these multiple equilibria ranging from the babbling equilibrium to the much more precise one. And it seems like, if I’m trying to communicate with Seth costlessly, and all costly signal has been destroyed so we only have cheap talk, the LLM could put us on a more communicative equilibrium.Seth: We could say more if we’re at the level where you trust me. The LLM can tell you more facts than I ever could.Bo Cowgill: Right. Put us into those more fine partitions in the cheap talk literature. At least that’s how I think the potential for it to help would go.Andrey: I wanna jump in a little bit because I’m a little bit worried for our listeners if we have to go through eight...Seth: You’re gonna love these functions, dude. They’re gonna love... this is gonna be the highlight of the episode.Andrey: I guess rather than having a discussion after every single one, I think it’s just good to list them and then we can talk.Seth: Okay. That’ll help Bo at least. I don’t know if the audience needs this; the audience is up to date with all the most lame postmodern literature. So for the sake of Bo, though, I’ll give you the six functions plus two bonus functions.* Informational: Literal truth.* Expressive (or Emotive): Expressing something about the sender. This is what actually seems to break in your paper: I can’t express that I’m a good worker bee if now everybody can easily express they’re good worker bees.* Connotative (or Directive): The rhetorical element. That’s the “I am going to figure out how to flatter you and persuade you,” not necessarily on a factual level. That’s the zero-sum game maybe you were just talking about.* Phatic: This is funny. This is the language used to just maintain communications. So the way I’m thinking about this is if we’re in an automated setting, you know how they have those “dead man’s switches” where it’s like, “If I ever die, my lawyer will send the information to the federal government.” And so you might have a message from your heart being like, “Bo’s alive. Bo’s alive. Bo’s alive.” And then the problem is when the message doesn’t go.* Metalingual (or Metalinguistic): Language to talk about language. You can tell me if you think LLMs have anything to help us with there.* Poetic: Language as beautiful for the sake of language. Maybe LLMs will change how beautiful language is.* Performative: This comes to us from John Searle, who talks about, “I now pronounce you man and wife.” That’s a function of language that is different than conveying information. It’s an act. And maybe LLMs can or can’t do those acts.* Incantatory (Magic): The most important function. Doing magic. You can come back to us about whether or not LLMs are capable of magic.Okay? So there’s eight functions of language for you. LLMs gonna change language? All right. Take any of them, Bo.Andrey: Seth, can I reframe the question? I try to be more grounded in what might be empirically falsifiable. We have these ideas that in certain domains—and we can focus on the jobs one—LLMs are going to be writing a lot of the language that was previously written by humans, and presumably the human that was sending the signal. So how is that going to affect how people find jobs in the future? And how do we think this market is gonna adjust as a result? Do you have any thoughts on that?Bo Cowgill: Yeah. So I guess the reframing is about how the market as a whole will adjust on both sides?Andrey: Yes, exactly.Bo Cowgill: Well, one, we have some survey results about this in the paper. It suggests you would shift towards more costly signals, maybe verifiable things like, “Where did you go t

In this episode, we brought on our friend Bo Cowgill, to dissect his forthcoming Management Science paper, Does AI Cheapen Talk? The core question is one economists have been circling since Spence drew a line on the blackboard: What happens when a technology makes costly signals cheap? If GenAI allows anyone to produce polished pitches, résumés, and cover letters, what happens to screening, hiring, and the entire communication equilibrium?Bo’s answer: it depends. Under some conditions, GenAI induces an epistemic apocalypse, flattening signals and confusing recruiters. In others, it reveals skill even more sharply, giving high-types superpowers. The episode walks through the theory, the experiment, and implications.Transcript:Seth: Welcome to the Justified Posteriors Podcast, the podcast that updates its priors about the economics of AI and technology. I’m Seth Benzell, certifying my humanity with takes so implausible that no softmax could ever select them at Chapman University in sunny Southern California.Andrey: And I am Andrey Fradkin, collecting my friends in all sorts of digital media formats, coming to you from San Francisco, California. Today we’re very excited to have Bo Cowgill with us. Bo is a friend of the show and a listener of the show, so it’s a real treat to have him. He is an assistant professor at Columbia Business School and has done really important research on hiring, on prediction markets, and now on AI and the intersection of those topics. And he’s also won some very cool prizes. I’ll mention that he was on the list of the best 40 business school professors. So he is one of those professors that’s really captivating for his students. So yeah. Welcome, Bo.Bo Cowgill: Thank you so much. It’s awesome to be here. Thanks so much for having me on the podcast.Seth: What do you value about the podcast? That’s something I’ve been trying to figure out because I just do the podcast for me. I’m just having a lot of fun here with Andrey. Anything I can do to get this guy’s attention to talk about interesting stuff for 10 minutes? Why do you like the podcast? What can we do to make this an even better podcast for assistant professors at Columbia?Bo Cowgill: Well, I don’t wanna speak for all assistant professors at Columbia, but one thing it does well is aggregate papers about AI that are coming out from around the ecosystem and random places. I think it’s hard for anybody to catch all of these, so you guys do a great job. I did learn about new papers from the podcast sometimes.Another cool thing I think is there is some continuity across podcast episodes about themes and arbitrage between different topics and across even different disciplines and domains. So I think this is another thing you don’t get necessarily just kind of thumbing around papers yourself.Seth: So flattering. So now I can ask you a follow-up question, which is: obviously you’re enjoying our communication to you. A podcast is kind of a one-dimensional communication. Now we’ve got the interview going, we’ve got this back and forth. How would you think about the experience of the podcast changing if a really, really, really good AI that had read all of my papers and all of Andrey’s papers went and did the same podcast, same topics? How would that experience change for you? Would it have as much informative content? Would it have as much experiential value? How do you think about that?Bo Cowgill: Well, first of all, I do enjoy y’all’s banter back and forth. I don’t know how well an AI would do that. Maybe it would do a perfectly good job with that. I do enjoy the fact that—this is personal to me—but we know a lot of the same people. And in addition to other guests and other paper references, I like to follow some of the inside jokes and whatnot. I don’t know if that’s all that big of a deal for the average person. But I have listened to at least the latest version of NotebookLM and its ability to do a quote-unquote “deep dive podcast” on anything. And at least recently I’ve been pleased with those. I don’t know if you’ve ever tried putting in like a bad paper in theirs, and then it will of course just say, “Oh, this is the greatest paper. It’s so interesting.”Seth: Right.Bo Cowgill: You can.Seth: So that’s a little bit different, maybe slightly different than our approach.Bo Cowgill: Well, yeah, for sure. Although you can also tell NotebookLM to try to find problems and be a little bit more critical. And that I think works well too. But yeah, I don’t think we should try to replace you guys with robots just yet.Seth: We’re very highly compensated though. The opportunity cost of Andrey’s time, he could be climbing a mountain right now. Andrey, you take it up. Why are we doing this ourselves? Why isn’t an LLM doing this communication for us?Andrey: Well, mostly it’s because we have fun doing it, and so if the LLM was doing it, then we wouldn’t be having the fun.Seth: There you go. Well put. Experiential value of the act itself. Now, Bo, I did not bring up this question randomly. The reason I raised this question of how does AI modify communication... yeah, I used a softmax process, so it was not random. The reason I’m asking this question about how AI changes communication is because you have some recently accepted, forthcoming work at Management Science trying to bring some theory and empirics to the question of how LLMs change human communication, but now in the context of resumes and job search and job pitches. Do you want to briefly introduce the paper “Does AI Cheapen Talk?” and tell us about your co-authors?Bo Cowgill: Yeah, most definitely. So the paper is called “Does AI Cheapen Talk?”. It is with Natalia Berg-Wright, also at Columbia Business School, and with Pablo Hernandez Lagos, who is a professor at Yeshiva University. And what we’re looking at in this paper is the way people screen job candidates or screen entrepreneurs or, more abstractly, how they kind of screen generally. You could apply our model, I think, to lots of different things.But the core idea behind it kind of goes back to these models from Spence in the 1970s saying that costly signals are more valuable to try to separate types.Seth: Right. If I wanna become a full member of the tribe, I have to go kill a lion. Why is it important for me to kill a lion? It’s not important. The important part is I do a hard thing.Bo Cowgill: Exactly. Yeah. So maybe part of the key to this Spence idea that appears in our paper too is that it’s not just that the signal has to be costly, it has to be kind of differentially costly for different types of people. So maybe in your tribe, killing a lion is easy for tough guys like you, but for wimpier people or something, it’s prohibitively high. And so it’s like a test of your underlying cost parameter for killing lions or for being tough in general. So they go and do this. And I guess what you’re alluding to, which appears in a lot of cases, is the actual value of killing the lion is kind of irrelevant. It was just a test.And maybe one of the more potentially depressing implications of that is the idea that what we send our students to do in four-year degrees or even degrees like ours is really just as valuable as killing a lion, which is to say, you’re mainly revealing something about your own costs and your own type and your own skills, and the actual work doesn’t generate all that much value.Seth: Is education training or screening?Bo Cowgill: Right, right, right. Yes. I do think a good amount of it these days is probably screening, and maybe that’s especially true at the MBA level.Andrey: I would just say that, given the rate of hiring for MBAs, I’m not sure that the screening is really happening either. Maybe the screening is happening to get in.Bo Cowgill: What the screening function is now is like, can you get in as the ultimate thing?Seth: Right. And I think as you already suggest, the way this works can flip if there’s a change in opportunity costs, right? So maybe in the past, “Oh, I’m the high type. I go to college.” In the present, “I’m the high type. I’m gonna skip college, I’m gonna be an entrepreneur,” and now going to college is a low signal.Bo Cowgill: Yes. Exactly. So that’s kind of what’s going on in our model too. How are we applying this to job screening and AI? Well, you apply for a job, you have a resume, possibly a cover letter or, if you don’t have an old-fashioned cover letter, you probably have a pitch to a recruiter or to your friend who works at the company. And there are kind of elements of costly signaling in those pitches. So some people could have really smart-sounding pitches that use the right jargon and are kind of up to speed with regards to the latest developments in the industry or in the underlying technology or whatever. And those could actually be really useful signals because the only sort of person who would be up to speed is the one who finds it easy to follow all this information.Seth: Can I pause you for a second? Back before LLMs, when I was in high school, they helped me make a CV or a resume. It’s not like there was ever any monitoring that people had to write their own cover letters.Bo Cowgill: That’s really true. No, some people have said about our paper that this is a more general model of signal dilution, which was happening before AI and the internet and everything. And so one example of this might be SAT tutoring or other forms of help for high school students, like writing your resume for you. Where if something comes along—and this is where GenAI is gonna come in—but if anything comes along that makes it cheaper to produce signals that were once more expensive, at least for some groups, then that changes the informational content of the signal.Seth: If the tribe gets guns, it’s too easy to kill a lion.Bo Cowgill: Yeah. Then it just is too easy to kill the lions. But similar things I think have happened in the post-COVID era around the SATs. Maybe it’s become too easy, or so the t

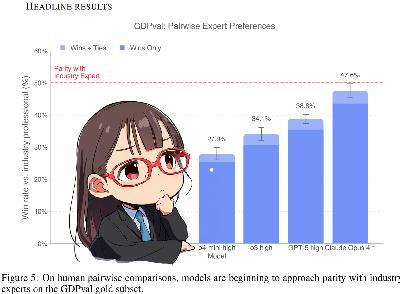

In this episode of Justified Posteriors podcast, Seth and Andrey discuss “GDPVal” a new set of AI evaluations, really a novel approach to AI evaluation, from OpenAI. The metric is debuted in a new OpenAI paper, “GDP Val: Evaluating AI Model Performance on Real-World, Economically Valuable Tasks.” We discuss this “bottom-up” approach to the possible economic impact of AI (which evaluates hundreds of specific tasks, multiplying them by estimated economic value in the economy of each), and contrast it with Daron Acemoglu’s “top-down” “Simple Macroeconomics of AI” paper (which does the same, but only for aggregate averages), as well as with measures of AI’s use and potential that are less directly tethered to economic value (like Anthropic's AI Economic Value Index and GPTs are GPTs). Unsurprisingly, the company pouring hundreds of billions into AI thinks that AI already can do ALOT. Perhaps trillions of dollars in knowledge work tasks annually. More surprisingly, OpenAI claims the leading Claude model is better than their own!Do we believe that analysis? Listen to find out!Key Findings & Results Discussed* AI Win Rate vs. Human Experts:* The Prior: We went in with a prior that a generic AI (like GPT-5 or Claude) would win against a paid human expert in a head-to-head task only about 10% of the time.* The Headline Result: The paper found a 47.6% win rate for Claude Opus (near human parity) and a 38.8% win rate for GPT-5 High. This was the most shocking finding for the hosts.* Cost and Speed Improvements:* The paper provides a prototype for measuring economic gains. It found that using GPT-5 in a collaborative “N-shot” workflow (where the user can prompt it multiple times) resulted in a 39% speed improvement and a 63% cost improvement over a human working alone.* The “Catastrophic Error” Rate:* A significant caveat is that in 2.7% of the tasks the AI lost, it was due to a “catastrophic error,” such as insulting a customer, recommending fraud, or suggesting physical harm. This is presumed to be much higher than the human error rate.* The “Taste” Problem (Human Agreement):* A crucial methodological finding was that inter-human agreement on which work product was “better” was only 70%. This suggests that “taste” and subjective preferences are major factors, making it difficult to declare an objective “winner” in many knowledge tasks. Main Discussion Points & Takeaways* The “Meeting Problem” (Why AI Can’t Take Over):* Andrey argues that even if AI can automate artifact creation (e.g., writing a report, making a presentation), it cannot automate the core of many knowledge-work jobs.* He posits that much of this work is actually social coordination, consensus-building, and decision-making—the very things that happen in meetings. AI cannot yet replace this social function.* Manager of Agents vs. “By Hand”:* The Prior: We believed 90-95% of knowledge workers would still be working “by hand” (not just managing AI agents) in two years.* The Posterior: We did not significantly change this belief. We distinguish between “1-shot” delegation (true agent management) and “N-shot” iterative collaboration (which they still classify as working “by hand”). We believe most AI-assisted work will be the iterative kind for the foreseeable future.* Prompt Engineering vs. Model Size:* We noted that the models were not used “out-of-the-box” but benefited from significant, expert-level prompt engineering.* However, we were surprised that the data seemed to show that prompt tuning only offered a small boost (e.g., ~5 percentage points) compared to the massive gains from simply using a newer, larger, and more capable model.* Final Posterior Updates:* AI Win Rate: We updated our 10% prior to 25-30%. We remain skeptical of the 47.6% figure.PS — Should our thumbnails have anime girls in them, or Andrey with giant eyes? Let us know in the comments!Timestamps:* (00:45) Today’s Topic: A new OpenAI paper (”GDP Val”) that measures AI performance on real-world, economically valuable tasks.* (01:10) Context: How does this new paper compare to Acemoglu’s “Simple Macroeconomics of AI”?* (04:45) Prior #1: What percentage of knowledge tasks will AI win head-to-head against a human? (Seth’s prior: 10%).* (09:45) Prior #2: In two years, what share of knowledge workers will be “managers of AI agents” vs. doing work “by hand”?* (19:25) The Methodology: This study uses sophisticated prompt engineering, not just out-of-the-box models.* (25:20) Headline Result: AI (Claude Opus) achieves a 47.6% win rate against human experts, nearing human parity. GPT-5 High follows at 38.8%.* (33:45) Cost & Speed Improvements: Using GPT-5 in a collaborative workflow can lead to a 39% speed improvement and a 63% cost improvement.* (37:45) The “Catastrophic Error” Rate: How often does the AI fail badly? (Answer: 2.7% of the time).* (39:50) The “Taste” Problem: Why inter-human agreement on task quality (at only 70%) is a major challenge for measuring AI.* (53:40) The Meeting Problem: Why AI can’t (yet) automate key parts of knowledge work like consensus-building and coordination.* (58:00) Posteriors Updated: Seth and Andrey update their “AI win rate” prior from 10% to 25-30%.Seth: Welcome to the Justified Posteriors Podcast, the podcast that updates its priors on the economics of AI and technology. I’m Seth Benzell, highly competent at many real-world tasks, just not the most economically valuable ones, coming to you from Chapman University in sunny Southern California.Andrey: And I’m Andrey Fradkin, making sure to never use the Unicode character 2011, since it will not render properly on people’s computers. Coming to you from,, San Francisco, California.Seth: Amazing, Andrey. Amazing to have you here in the “state of the future.” and today we’re kind of reading about those AI companies that are bringing the future here today and are gonna, I guess, automate all knowledge work. And here they are today, with some measures about how many jobs—how much economic value of jobs—they think current generation chatbots can replace. We’ll talk about to what extent we believe those economic extrapolations. But before we go into what happens in this paper from our friends at OpenAI, do you remember one of our early episodes, that macroeconomics of AI episode we did about Daron Acemoglu’s paper?Andrey: Well, the only thing I remember, Seth, is they were quite simple, those macroeconomics., it was the...Seth: “Simple Macroeconomics of AI.” So you remembered the title. And if I recall correctly, the main argument of that paper was you can figure out the productivity of AI in the economy by multiplying together a couple of numbers. How many jobs can be automated? Then you multiply it by, if you automate the job, how much less labor do you need? Then you multiply that by, if it’s possible to automate, is it economically viable to automate? And you multiply those three numbers together and Daron concludes that if you implement all current generation AI, you’ll raise GDP by one percentage point. If you think that’s gonna take 10 years, he concludes that’s gonna be 0.1 additional percentage point of growth a year. You can see why people are losing their minds over this AI boom, Andrey.Andrey: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, I, you know, I think with such so much hype, you know, they should,, they should,, probably just stop investing altogether. Is kind of right what I would think from [Eriun’s?] paper. Yeah.Seth: Well, Andrey, why don’t I tell you, which is, the way I see this paper that we just read is that OpenAI has actually taken on the challenge and said, “Okay, you can multiply three numbers together and tell me the economic value of AI. I’m gonna multiply 200 numbers together and tell you the economic value of AI.” And in particular, rather than just try to take the sort of global aggregate of like efficiency from automation, they’re gonna go task by task by task and try to measure: Can AI speed you up? Can it do the job by itself?, this is the sort of real-world economics rubber-hits-the-road that you don’t see in macroeconomics papers.Andrey: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, it is, it is in many ways a very micro study, but I guess micro...Seth: Macro.Andrey: Micro, macro. That was the best, actually my favorite.Seth: Yeah.Andrey: I guess maybe we should start with our prior, Seth,, before we get deeper.Seth: Well, let’s say the name of the paper and the authors maybe.Andrey: There are so many authors, so OpenAI... I’m sorry guys. You gotta have fewer co-authors.Seth: We will not list the authors.Andrey: But,, the paper is called,, “GDP Val: Evaluating AI Model Performance on Real-World, Economically Valuable Tasks.”Seth: And we’re sure it’s written by humans.Andrey: We’re sure that it’s not fully written by humans because they’ve disclosed that they use AI. They have an acknowledgement—they have an AI acknowledgement section.Seth: They used AI “as per usual”? Yeah. In the “ordinary course of coding...”Andrey: And writing.Seth: And writing. And for “minor improvements.” Yes. They wanted to be clear. Okay.Andrey: Not, not the major ones. Yes.Seth: Because,, you know, base... so, all right. You gave us the name of the paper. The paper is going to... just in one sentence, what the paper is about is them going through lots of different tasks and trying to figure out if they can be automated. What are the priors? Before we go into this, what are you thinking about, Andrey?Andrey: Well, what they’re gonna do is they’re gonna create a work product, let’s say a presentation or schematic or a document, and then they’re gonna have people rate which one is better, the one created by the AI, or the one created by a professional human being. And so the first prior that we have is: What share of time is the AI’s output gonna win? so what do you think, Seth?Seth: Great question. Okay, so I’m thinking about the space of all knowledge work in the economy. All of the jobs done by humans that we think you could do 100% on a computer,

In this episode, Seth Benzell and Andrey Fradkin read “We Won’t Be Missed: Work and Growth in the AGI World” by Pascual Restrepo (Yale) to understand what how AGI will change work in the long run. A common metaphor for the post AGI economy is to compare AGIs to humans and men to ants. Will the AGI want to keep the humans around? Some argue that they would — there’s the possibility of useful exchange with the ants, even if they are small and weak, because an AGI will, definitionally, have opportunity costs. You might view Pascual’s paper as a formalization of this line of reasoning — what would be humanity’s asymptotic marginal product in a world of continually improving super AIs? Does the God Machine have an opportunity cost?Andrey, our man on the scene, attended the NBER Economics of Transformative AI conference to learn more from Pascual Restrepo, Seth’s former PhD committee member.We compare Restrepo’s stripped-down growth logic to other macro takes, poke at the tension between finite-time and asymptotic reasoning, and even detour into a “sheep theory” of monetary policy. If compute accumulation drives growth, do humans retain any essential production role—or only inessential, “cherry on top” accessory ones?Relevant Links* We Won’t Be Missed: Work and Growth in the AGI World — Pascual Restrepo (NBER TAI conference) and discussant commentary* NBER Workshop Video: “We Won’t Be Missed” (Sept 19 2025)* Marc Andreessen, Why Software Is Eating the World (WSJ 2011)* Shapiro & Varian, Information Rules: A Strategic Guide to the Network Economy (HBR Press)* Ecstasy: Understanding the Psychology of Joy — Find the sheep theory of the price level here: Seth’s ReviewPriors and PosteriorsClaim 1 — After AGI, the labor share goes to zero (asymptotically)* Seth’s prior: >90% chance of a large decline, <10% chance of literally hitting ~0% within 100 years.* Seth’s posterior: Unchanged. Big decline likely; asymptotic zero still implausible in finite time.* Andrey’s prior: Skeptical that asymptotic results tell us much about a 100-year horizon.* Andrey’s posterior: Unchanged. Finite-time dynamics dominate.* Summary: Compute automates bottlenecks, but socially or physically constrained “accessory” human work probably keeps labor share above zero for centuries.Claim 2 — Real wages 100 years after AGI will be higher than today* Seth’s prior: 70% chance real wages rise within a century of AGI.* Seth’s posterior: 71% (a tiny uptick).* Andrey’s prior: Agnostic; depends on transition path.* Andrey’s posterior: Still agnostic.* Summary: If compute accumulation drives growth and humans still trade on preference-based or ritual tasks, real wages could rise even as labor’s income share collapses.Keep your Apollonian separate from your Dionysian—and your accessory work bottlenecked.Timestamps:[00:01:47] NBER Economics of Transformative AI Conference [00:04:21] Pascual Restrepo’s paper on automation and AGI [00:05:28] Will labor share go to zero after AGI? [00:43:52] Conclusions and updating posteriors [00:48:24] Second claim: Will wages go down after AGI? [00:50:00] The sheep theory of monetary policyTranscript[00:00:00] Seth: Welcome everyone to the Justified Posteriors Podcast, where we read technology and economics papers and get persuaded by them so you don’t have to.Welcome to the Justified Posteriors Podcast, the podcast that updates its priors about the economics of AI and technology. I’m Seth Benzell performing bottleneck tasks every day in the sense that I’m holding a bottle and a baby by the neck down in Chapman University in sunny, Southern California. [00:00:40] Andrey: I’m Andrey Fradkin, practicing my accessory tasks even before the AGI comes coming to you from San Francisco, California.So Seth, great [00:00:53] Seth: to be. Yeah, please. [00:00:54] Andrey: Well, what are you, what have you been thinking about recently? What have been, [00:01:00] contemplating. [00:01:01] Seth: Well, you know, having a baby gets you to think a lot about, what’s really important in life and what kind of future are we leaving to him, you know, if we might imagine a hundred years from now, what is the economy that he’s gonna have when he’s retired?Who even knows what such a future would look like? And a lot of economists are asking this question and there was this really kind of cool conference that put together some of the favorite friends of the show. An NBER Economics of Transformative AI Conference that forced participants to accept the premise that AGI is invented.Okay, go do economics of that. And Andrey, I hear that somehow you were able to get the inside scoop. [00:01:47] Andrey: Yes. Um, it was a pleasure to contribute a paper with some co-authors to the conference and to attend. It was really fun to [00:02:00] just hear how people are, um, thinking about these things, people who oftentimes I associate with being very kind of serious, empirical, rigorous people kind of thinking pie in the sky thoughts about transformative AI.So, yeah, it was a lot of fun. Um, and there were a lot of interesting papers. [00:02:22] Seth: Go ahead. Wait. No, before I want, I’m not gonna let you off the hook Andrey. Yeah, because I have to say, just before we started the show, you did not present all of the conversation at the seminars as a hundred percent fun as enlightening, but rather you found some of the debate a little bit frustrating.Why? Why is that? [00:02:39] Andrey: Well, I mean, I, you know, dear listeners, I hope we don’t fall guilty of this, but I do find a lot of AI conversation to be a little cliche and hackneyed at this point. Right. It’s kind of surprising how little [00:03:00] new stuff can be said. If you’ve read some science fiction books, you kind of know the potential outcomes.Um, and so, you know, it’s a question of what we as a community of economists can offer that’s useful or new. And I do think we can, it’s just, it’s very easy to fall into these cliches or well trodden paths. [00:03:20] Seth: What? What’s the meaning of life? Andrey? Will life have meaning after the robot takes my job? Will my AI girlfriend really fulfill me?Why do we think economists would be good at answering those questions? [00:03:34] Andrey: Yeah, it’s a great question, Seth. I’m not sure. Um, [00:03:39] Seth: I think it’s because they’re the last respected kind of technocrat. Obviously all technocrats are hated, but if anybody’s allowed to have an opinion about whether your anime cat girl waifu AI companion is truly fulfilling.We’re the only, we’re the only source of remaining authority. [00:03:57] Andrey: Well, you know, [00:03:57] Seth: unfortunately, [00:03:58] Andrey: I think it’s a [00:04:00] common thing to speculate as to which profession will be automated last, and certainly Marc Andreessen believes that it is venture capitalist. So [00:04:11] Seth: Fair enough. I’ll narcissism, I’ll leave [00:04:13] Andrey: it as an exercise to the listener what economists think.[00:04:21] Seth: So let’s talk about, so we’re, we’re at, we’re talking about whether humans will be essential in the long run because the particular paper that struck my eye when I was looking at the list of seminars topics was a paper by friend of the show, I hope he considers us a friend of the show because I love this guy.Pascual Restrepo, a professor of economics and AI at Yale University. Um, had the honor of having this guy on my dissertation committee was definitely a role model when I was a young gun, trying to think about macro of AI before everyone on earth was thinking about macro of AI. [00:05:00] Um. And so it’s a real honor for the show to take on one of his papers and he’s got something that’s trying to respond to.Okay. Transformative AI shows up. What are the long-term dynamics of that? Which is a departure from where he wants to be. He wants to live in near future. We automate another 10% of tasks land. Right. So I was excited to take this on. Um, Andrey, do you wanna maybe, introduce some of the questions it asks us to consider?[00:05:28] Andrey: Yeah. So, Pascual presents a very stylized model of the macro economy and we picked two claims from the paper to think about in terms of our priors. Um, the first one of these is, um, after we get AGI in the limit, the labor share will go to zero. That is the first claim of this paper. Um, what do you think about that, Seth?[00:05:59] Seth: Great question. [00:06:00] Um, so to remind listeners, so the labor share is if you imagine all of the payments in the economy, some are going to workers and then some are going to people who own the machines or own the AI, right? So today about two thirds of the money or about 60% of the money is paid to workers.About 40% is paid to machines and out to profits and people who own stuff. It is a claim of this paper and a kind of a lot, a theme of a lot of the automation literature that as you get more and more automation, you’d expect the share of monies that are being paid to workers to go down, right? Because just more of the economy is just automation unconstrained by.Um, let me tell you how I think about this question, Andrey. First of all, you know, we’re not gonna talk about out to infinity. I know these are asymptotic papers, but let’s try to stay a little bit closer. Um, so I’ll, I’ll mostly be thinking about like a hundred years after [00:07:00] AGI, right? So we have AGI, and now we’re, we’ve played it out in some sense.We’ve had the next industrial revolution that happens from AGI, right? Assuming we don’t have an apocalypse, so this is, let’s set aside, conditional on, you know, we don’t destroy ourselves, which I don’t think there’s a huge chance of that, but that’s another question. I would say there’s a greater than 90% chance of very large decreases in labor share, you know, down from 60% today to 5%, 10%, 20%.I really do see that. But I think there’s like a less than a 10% chance that within a hundred years of AGI, um, we’ll have, you know, literally 0% labor share or what

Economists generally see AI as a production technology, or input into production. But maybe AI is actually more impactful as unlocking a new way of organizing society. Finish this story: * The printing press unlocked the Enlightenment — along with both liberal democracy and France’s Reign of Terror* Communism is primitive socialism plus electricity* The radio was an essential prerequisite for fascism * AI will unlock ????We read “AI as Governance” by Henry Farrell in order to understand whether and how political scientists are thinking about this question. * Concepts or other books discussed:* E. Glen Weyl, coauthor of Radical Markets: Uprooting Capitalism and Democracy for a Just Society, and key figure in the Plurality Institute was brought up by Seth as an example of an economist-political science crossover figure who is thinking about using technology to radically reform markets and governance. * Cybernetics: This is a “science” that studies human-technological systems from an engineering perspective. Historically, it has been implicated in some fantastic social mistakes, such as China’s one-child policy.* Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem: The economic result that society may not have rational preferences — if true, “satisfying social preferences” may not be a possible goal to maximize * GovAI - Centre for the Governance of AI* Papers on how much people/communication is already being distorted by AI:* Previous episode mentioned in the context of AI for social control:* Simulacra and Simulation (Baudrillard): Baudrillard (to the extent that any particular view can be attributed to someone so anti-reality) believed that society lives in “Simulacra”. That is, artificially, technologically or socially constructed realities that may have some pretense of connection to ultimate reality (i.e. a simulation) but are in fact completely untethered fantasy worlds at the whim of techno-capitalist power. A Keynesian economic model might be a simulation, whereas Dwarf Fortress is a simulacra (a simulation of something that never existed). Whenever Justified Posteriors hears “governance as simulation”, it thinks: simulation or simulacra?Episode Timestamps[00:00:00] Introductions and the hosts’ backgrounds in political science. [00:04:45] Introduction of the core essay: Henry Farrell’s “AI as Governance.” [00:05:30] Stating our Priors on AI as Governance[00:15:30] Defining Governance (Information processing and social coordination). [00:19:45] Governance as “Lossy Simulations” (Markets, Democracy, Bureaucracy). [00:25:30] AI as a tool for Democratic Consensus and Preference Extraction. [00:28:45] The debate on Algorithmic Bias and cultural bias in LLMs. [00:33:00] AI as a Cultural Technology and the political battles over information. [00:39:45] Low-cost signaling and the degradation of communication (AI-generated resumes).[00:43:00] Speculation on automated Cultural Battles (AI vs. AI). [00:51:30] Justifying Posteriors: Updating beliefs on the need for a new political science. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit empiricrafting.substack.com

Many of today’s thinkers and journalists worry that AI models are eating their lunch: hoovering up these authors’ best ideas and giving them away for free or nearly free. Beyond fairness, there is a worry that these authors will stop producing valuable content if they can’t be compensated for their work. On the other hand, making lots of data freely accessible makes AI models better, potentially increasing the utility of everyone using them. Lawsuits are working their way through the courts as we speak of AI with property rights. Society needs a better of understanding the harms and benefits of different AI property rights regimes.A useful first question is “How much is the AI actually remembering about specific books it is illicitly reading?” To find out, co-hosts Seth and Andrey read “Cloze Encounters: The Impact of Pirated Data Access on LLM Performance”. The paper cleverly measures this through how often the AI can recall proper names from the dubiously legal “Book3” darkweb data repository — although Andrey raises some experimental concerns. Listen in to hear more about what our AI models are learning from naughty books, and how Seth and Andrey think that should inform AI property rights moving forward. Also mentioned in the podcast are: * Joshua Gans paper on AI property rights “Copyright Policy Options for Generative Artificial Intelligence” accepted at the Journal of Law and Economics: * Fair Use* The Anthropic lawsuit discussed in the podcast about illegal use of books has reached a tentative settlement after the podcast was recorded. The headline summary: “Anthropic, the developer of the Claude AI system, has agreed to a proposed $1.5 billion settlement to resolve a class-action lawsuit, in which authors and publishers alleged that Anthropic used pirated copies of books — sourced from online repositories such as Books3, LibGen, and Pirate Library Mirror — to train its Large Language Models (LLMs). Approximately 500,000 works are covered, with compensation set at approximately $3,000 per book. As part of the settlement, Anthropic has also agreed to destroy the unlawfully obtained files.”* Our previous Scaling Law episode: This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit empiricrafting.substack.com

In our first ever EMERGENCY PODCAST, co-host Seth Benzell is summoned out of paternity leave by Andrey Fradkin to discuss the AI automation paper that’s making headlines around the world. The paper is Canaries in the Coal Mine? Six Facts about the Recent Employment Effects of Artificial Intelligence by Erik Brynjolfsson, Bharat Chandar, and Ruyu Chen. The paper is being heralded as the first evidence that AI is negatively impacting employment for young workers in certain careers. Seth and Andrey dive in, and ask — what do we believe about AI’s effect on youth employment going in, and what can we learn from this new evidence? Related recent paper on AI and job postings: Generative AI as Seniority-Biased Technological Change: Evidence from U.S. Résumé and Job Posting Data Also related to our discussion is the China Shock literature, which Nick Decker summarizes in his blog post: This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit empiricrafting.substack.com

In this episode, we discuss a new theoretical framework for understanding how AI integrates into the economy. We read the paper Artificial Intelligence and the Knowledge Economy (Ide & Talamas, JPE), and debate whether AI will function as a worker, a manager, or an expert. Read on to learn more about the model, our thoughts, timestamp, and at the end, you can spoil yourself on Andrey and Seth’s prior beliefs and posterior conclusions — Thanks to Abdullahi Hassan for compiling these notes to make this possible. The Ide & Talamas ModelOur discussion was based on the paper Artificial Intelligence in the Knowledge Economy by Enrique Ide and Eduard Talamas. It is a theoretical model of organizational design in the age of AI. Here’s the basic setup:* The Setting: A knowledge economy where firms’ central job is solving a continuous stream of problems.* The Players: We have Workers (human or AI) and a higher-level Solver (human manager/expert or AI). Crucially, the human players are vertically differentiated—they have different skill levels.* The Workflow: It’s a two-step process: A worker gets the first shot at solving the problem. If they fail, the problem gets escalated up the hierarchy to the Solver for a second attempt.* The Core Question: Given this hierarchy, what’s the most efficient organizational arrangement as AI gets smarter? Do we pair human workers with an AI manager, or go for the AI worker/human manager combo? * There are also possibilities not considered in the paper, such as chains of alternating managers and employees, something more network-y etc. Key Debates & CritiquesHere are the most interesting points of agreement, disagreement, and analysis we wrestled with:* Is a Solver Really a Manager? We spent a lot of time critiquing the paper’s terminology. The “manager” in this model is really an Expert who handles difficult exceptions. We argued that this role doesn’t capture the true human elements of management, like setting strategic direction, building team culture, or handling hiring/firing.* My Desire vs. Societal Growth: Andrey confessed that while he personally wants an AI worker to handle all the tedious stuff (like coding and receipts), the economy might see better growth and reduced inequality from having AI experts and managers who can unlock new productivity at the highest levels.* The Uber Driver Problem: We debate how to classify jobs like Uber driving. Is this already an example of AI managing the human (high-frequency algorithmic feedback), or is the driver still an entrepreneur who will manage their own fleet of smaller AI agents for administrative tasks?Go DeeperCheck out the sources we discussed for a deeper dive:* Main Paper: Artificial Intelligence and the Knowledge Economy (Ide & Talamas, JPE)* Mentioned Research: Generative AI at Work (Brynjolfsson, Lee, & Raymond on AI in call centers)Timestamps* [00:00] Worker, Manager, or Expert?* [00:06] Who manages the AI agents?* [00:15] Will AI worsen inequality?* [00:25] The Ide & Talamas model explained* [00:40] Limitations and critiques* [00:55] Posteriors: updated beliefsThe Bets: Priors & PredictionsWe pinned down our initial beliefs on two key questions about the future impact of AI agents, the foundation of our “Justified Posteriors.”Prediction 1: Will Managing AI Agents Become a Common Job? What percentage of U.S. workers will have “managing or creating teams of AI agents” as their main job within 5 years?Prediction 2: Will LLM-based Agents Exacerbate Wage Polarization?* Seth’s Prior: 25% chance it WILL exacerbate. Reasoning: Emerging evidence (like the call center study)* Andre’s Prior: 55% chance it WILL exacerbate. Reasoning: Skeptical of short-term studies; believes historical technology trends favor high-skill workers who capture the largest gains.Our Final PosteriorsPrediction 1: Will Managing AI Agents Become a Common Job?The model slightly convinced Seth that the high-skill vertical differentiation story might be stronger than he initially believed, leading to a small increase in his posterior for exacerbation. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit empiricrafting.substack.com