Scaling Laws Meet Persuasion

Description

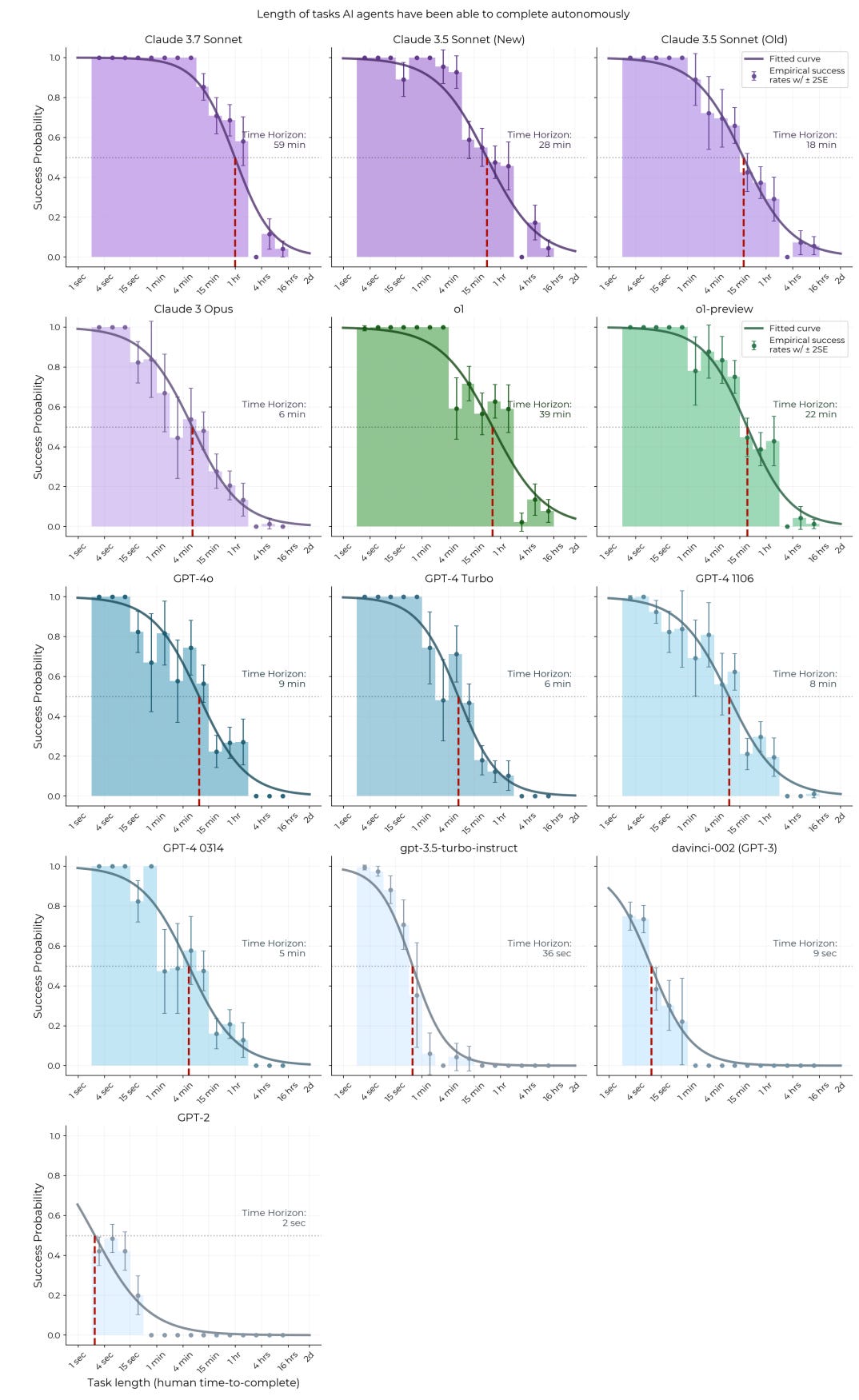

In this episode, we tackle the thorny question of AI persuasion with a fresh study: "Scaling Language Model Size Yields Diminishing Returns for Single-Message Political Persuasion." The headline? Bigger AI models plateau in their persuasive power around the 70B parameter mark—think LLaMA 2 70B or Qwen-1.5 72B.

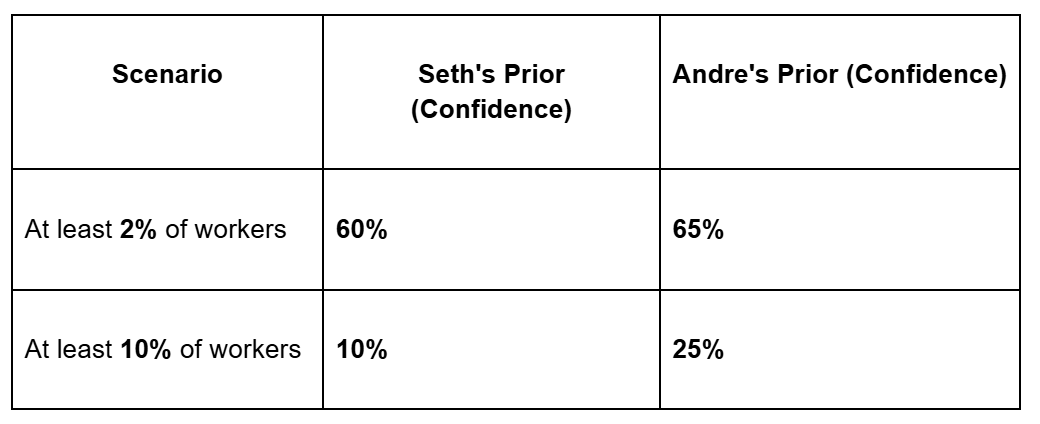

As you can imagine, this had us diving deep into what this means for AI safety concerns and the future of digital influence. Seth came in worried that super-persuasive AIs might be the top existential risk (60% confidence!), while Andrey was far more skeptical (less than 1%).

Before jumping into the study, we explored a fascinating tangent: what even counts as "persuasion"? Is it pure rhetoric, mathematical proof, or does it include trading incentives like an AI offering you money to let it out of the box? This definitional rabbit hole shaped how we thought about everything that followed.

Then we broke down the study itself, which tested models across the size spectrum on political persuasion tasks. So where did our posteriors land on scaling AI persuasion and its role in existential risk? Listen to find out!

🔗Links to the paper for this episode's discussion:

* (FULL PAPER) Scaling Language Model Size Yields Diminishing Returns for Single-Message Political Persuasion by Kobe Hackenberg, Ben Tappin, Paul Röttger, Scott Hale, Jonathan Bright, and Helen Margetts

🔗Related papers we discussed:

* Durably Reducing Conspiracy Beliefs Through Dialogues with AI by Costello, Pennycook, and David Rand - showed 20% reduction in conspiracy beliefs through AI dialogue that persisted for months

* The controversial Reddit "Change My View" study (University of Zurich) - found AI responses earned more "delta" awards but was quickly retracted due to ethical concerns

* David Shor's work on political messaging - demonstrates that even experts are terrible at predicting what persuasive messages will work without extensive testing

(00:00 ) Intro

(00:37 ) Persuasion, Identity, and Emotional Resistance

(01:39 ) The Threat of AI Persuasion and How to Study It

(05:29 ) Registering Our Priors: Scaling Laws, Diminishing Returns, and AI Capability Growth

(15:50 ) What Counts as Persuasion? Rhetoric, Deception, and Incentives

(17:33 ) Evaluation & Discussion of the Main Study (Hackenberg et al.)

(24:08 ) Real-World Persuasion: Limits, Personalization, and Marketing Parallels

(27:03 ) Related Papers & Research

(34:38 ) Persuasion at Scale and Equilibrium Effects

(37:57 ) Justifying Our Posteriors

(39:17 ) Final Thoughts and Wrap Up

🗞️Subscribe for upcoming episodes, post-podcast notes, and Andrey’s posts:

💻 Follow us on Twitter:

@AndreyFradkin https://x.com/andreyfradkin?lang=en

@SBenzell https://x.com/sbenzell?lang=en

Transcript:

AI Persuasion

Seth: Justified Posteriors podcast, the podcast that updates beliefs about the economics of AI and technology. I'm Seth Benzel, possessing superhuman levels in the ability to be persuaded, coming to you from Chapman University in sunny Southern California.

Andrey: And I'm Andrey Fradkin, preferring to be persuaded by the 200-word abstract rather than the 100-word abstract, coming to you from rainy Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Seth: That's an interesting place to start. Andrey, do you enjoy being persuaded? Do you like the feeling of your view changing, or is it actually unpleasant?

Andrey: It depends on whether that view is a key part of my identity. Seth, what about yourself?

Seth: I think that’s fair. If you were to persuade me that I'm actually a woman, or that I'm actually, you know, Salvadoran, that would probably upset me a lot more than if you were to persuade me that the sum of two large numbers is different than the sum that I thought that they summed to. Um.

Andrey: Hey, Seth, I found your birth certificate...

Seth: No.

Andrey: ...and it turns out you were born in El Salvador.

Seth: Damn. Alright, well, we're gonna cut that one out of the podcast. If any ICE officers hear about this, I'm gonna be very sad. But that brings up the idea, right? When you give someone either information or an argument that might change the way they act, it might help them, it might hurt them. And I don't know if you've noticed, Andrey, but there are these new digital technologies creating a lot of text, and they might persuade people.

Andrey: You know, there are people going around saying these things are so persuasive, they’re going to destroy society. I don’t know...

Seth: Persuade us all to shoot ourselves, the end. One day we’ll turn on ChatGPT, and the response to every post will be this highly compelling argument about why we should just end it now. Everyone will be persuaded, and then the age of the machine. Presumably that’s the concern.

Andrey: Yes. So here's a question for you, Seth. Let's say we had this worry and we wanted to study it.

Seth: Ooh.

Andrey: How would you go about doing this?

Seth: Well, it seems to me like I’d get together a bunch of humans, try to persuade them with AIs, and see how successful I was.

Andrey: Okay, that seems like a reasonable idea. Which AI would you use?

Seth: Now that's interesting, right? Because AI models vary along two dimensions. They vary in size, do you have a model with a ton of parameters or very few? and they also vary in what you might call taste, how they’re fine-tuned for particular tasks. It seems like if you want to persuade someone, you’d want a big model, because we usually think bigger means more powerful, as well as a model that’s fine-tuned toward the specific thing you’re trying to achieve. What about you, Andrey?

Andrey: Well, I’m a little old-school, Seth. I’m a big advocate of the experimentation approach. What I would do is run a bunch of experiments to figure out the most persuasive messages for a certain type of person, and then fine-tune the LLM based on that.

Seth: Right, so now you’re talking about micro-targeting. There are really two questions here: can you persuade a generic person in an ad, and can you persuade this person, given enough information about their context?

Andrey: Yeah. So with that in mind, do we want to state what the questions are in the study we’re considering in this podcast?

Seth: I would love to. Today, we’re studying the question of how persuasive AIs are. And more importantly, or what gives this question particular interest, is not just can AI persuade people, because we know anything can persuade people. A thunderstorm at the right time can persuade people. A railroad eclipse or some other natural omen. Rather, we’re asking: as we make these models bigger, how much better do they get at persuading people? That’s the key, this flavor of progression over time.

If you talk to Andrey, he doesn’t like studies that just look at what the AI is like now. He wants something that gives you the arrow of where the AI is going. And this paper is a great example of that. Would you tell us the title and authors, Andrey?

Andrey: Sure. The title is Scaling Language Model Size Yields Diminishing Returns for Single-Message Political Persuasion by Kobe Hackenberg, Ben Tappin, Paul Röttger, Scott Hale, Jonathan Bright, and Helen Margetts. Apologies to the authors for mispronouncing everyone’s names.

Seth: Amazing. A crack team coming at this question. Maybe before we get too deep into what they do, let’s register our priors and tell the audience what we thought about AI persuasion as a potential thing, as an existential risk or just a regular risk. Let’s talk about our views.

Seth: The first prior we’re considering is: do we think LLMs are going to see reducing returns to scale from increases in parameter count? We all think a super tiny model isn’t going to be as powerful as the most up-to-date, biggest models, but are there diminishing returns to scale? What do you think of that question, Andrey?

Andrey: Let me throw back to our Scaling Laws episode, Seth. I do believe the scaling laws everyone talks about exhibit diminishing returns by definition.

Seth: Right. A log-log relationship... wait, let me think about that for a second. A log-log relationship doesn’t tell you anything about increasing returns...

Andrey: Yeah, that’s true. It’s scale-free, well, to the extent that each order of magnitude costs an order of magnitude more, typically.

Seth: So whether the returns are increasing or decreasing depends on which number is bigger to start with.

Andrey: Yes, yes.

Seth: So the answer is: you wouldn’t