One LLM to rule them all?

Description

In this special episode of the Justified Posteriors Podcast, hosts Seth Benzell and Andrey Fradkin dive into the competitive dynamics of large language models (LLMs). Using Andrey’s working paper, Demand for LLMs: Descriptive Evidence on Substitution, Market Expansion, and Multihoming, they explore how quickly new models gain market share, why some cannibalize predecessors while others expand the user base, and how apps often integrate multiple models simultaneously.

Host’s note, this episode was recorded in May 2025, and things have been rapidly evolving. Look for an update sometime soon.

Transcript

Seth: Welcome to Justified Posterior Podcast, the podcast that updates beliefs about the economics of AI and technology. I'm Seth Benzel, possessing a highly horizontally differentiated intelligence—not saying that's a good thing—coming to you from Chapman University in sunny Southern California.

Andrey: And I'm Andrey Fradkin, multi-homing across many different papers I'm working on, coming to you from sunny—in this case—Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Seth: Wow…. Rare, sunny day in Cambridge, Mass. But I guess the sunlight is kind of a theme for our talk today because we're going to try to shed some light on some surprising features of AI, some important features, and yet, not discussed at all. Why don't people write papers about the important part of AI? Andrey, what's this paper about?

Andrey: I agree that not enough work has been done on this very important topic. Look, we can think about the big macroeconomic implications of AI—that's really fun to talk about—but it's also fun to talk about the business of AI. Specifically, who's going to win out? Which models are better than others? And how can we measure these things as they're happening at the moment? And so that's really what this paper is about. It's trying to study how different model providers compete with each other.

Seth: Before we get deep into that—I do want to push back on the idea that this isn't macroeconomically important. I think understanding the kind of way that the industry structure for AI will work will have incredible macroeconomic implications, right? If only for diversity—for equality across countries, right? We might end up in a world where there's just one country or a pair of countries that dominate AI versus a world where the entire world is involved in the AI supply chain and plugging in valuable pieces, and those are two very different worlds.

Andrey: Yeah. So, you're speaking my book, Seth. Being an industrial organization economist, you know, we constantly have this belief that macroeconomists, by thinking so big-picture, are missing the important details about specific industries that are actually important for the macroeconomy.

Seth: I mean—not every specific industry; there's one or two specific industries that I would pay attention to.

Andrey: Have you heard of the cereal industry, Seth?

Seth: The cereal industry?

Andrey: It's important how mushy the cereal is.

Seth: Well, actually, believe it or not, I do have a breakfast cereal industry take that we will get to before the end of this podcast. So, viewers [and] listeners at home, you gotta stay to the end for the breakfast cereal AI economics take.

Andrey: Yeah. And listeners at home, the reason that I'm mentioning cereal is it's of course the favorite. It's the fruit fly of industrial organization for estimating demand specifically. So—a lot of papers have been written about estimating serial demand and other such things

Seth: Ah—I thought it was cars. I guess cars and cereal are the two things.

Andrey: Cars and cereal are the classic go-tos.

Introducing the paper

Seth: Amazing. So, what [REDACTED] wrote the paper we're reading today, Andrey?

Andrey: Well, you know—it was me, dear reader—I wrote the paper.

Seth: So we know who's responsible.

Andrey: All mistakes are my fault, but I should also mention that I wrote it in a week and it's all very much in progress. And so I hope to learn from this conversation, as we—let's say my priors are diffuse enough so that I can still update

Seth: Oh dude, I want you to have a solid prior so we can get at it. But I will say I was very, very inspired by this project, Andrey. I also want to follow in your footsteps. Well, maybe we'll talk about that at the end of the podcast as well. But maybe you can just tell us the title of your paper. Andrey,

Andrey: The title of the paper is Demand for LLMs, and now you're forcing me to remember the title of the—

Seth: If you were an AI, you would remember the title of the paper, maybe.

Andrey: The title of the paper is Demand for LLMs: Descriptive Evidence on Substitution Market Expansion and Multi-Homing. So, I will state three claims, which I do make in the paper.

Seth: Ooh, ooh.

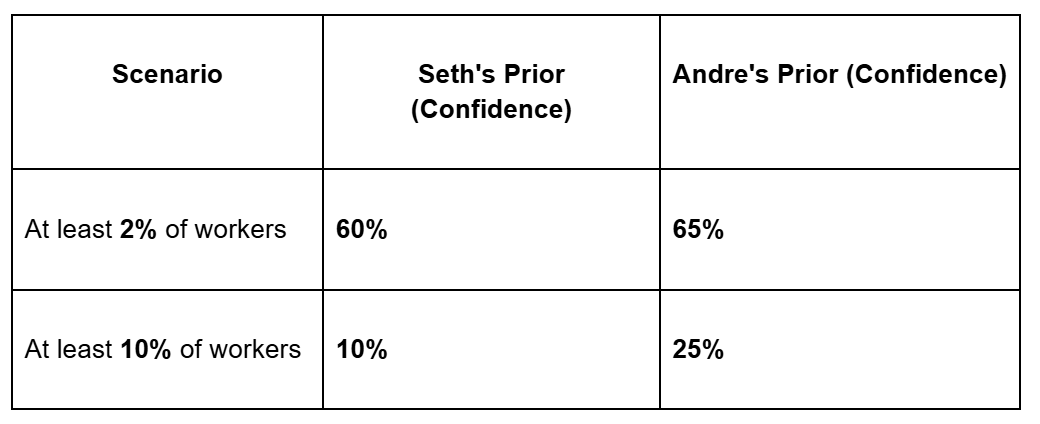

Andrey: And you can tell me your priors.

Seth: Prior on each one. Okay, so give me the abstract; claim number one.

Andrey: So the point number one is that when a new good model gets released, it gets adopted very quickly. Within a few weeks, it achieves kind of a baseline level of adoption. So I think that's fact number one. And that's very interesting because not all industries have such quick adoption cycles.

Seth: Right? It looks more like the movie or the media industry, where you have a release and then boom, everybody flocks to it. That's the sense that I got before reading this paper. So I would put my probability on a new-hot new model coming out; everybody starts trying it—I mean, a lot of these websites just push you towards the new model anyway.

I know we're going to be looking at a very specific context, but if we're just thinking overall. Man, 99% when a new hot new model comes out, people try it.

Andrey: So I'll push back on that. It's the claim that it's not about trying it, like these models achieve an equilibrium level of market penetration. It's not—

Seth: How long? How long is—how long is just trying it? Weeks, months.

Andrey: How long are—sorry, can you repeat that question?

Seth: So you're pushing back on the idea that this is, quote unquote, “just trying the new release.” Right. But what is the timeline you're looking over?

Andrey: It's certainly a few months, but it doesn't take a long time to just try it. So, if it was just trying we'd see us blip over a week, and then it would go back down. And I don't—

Seth: If they were highly horizontally differentiated, but if they were just very slightly horizontally differentiated, you might need a long time to figure it out.

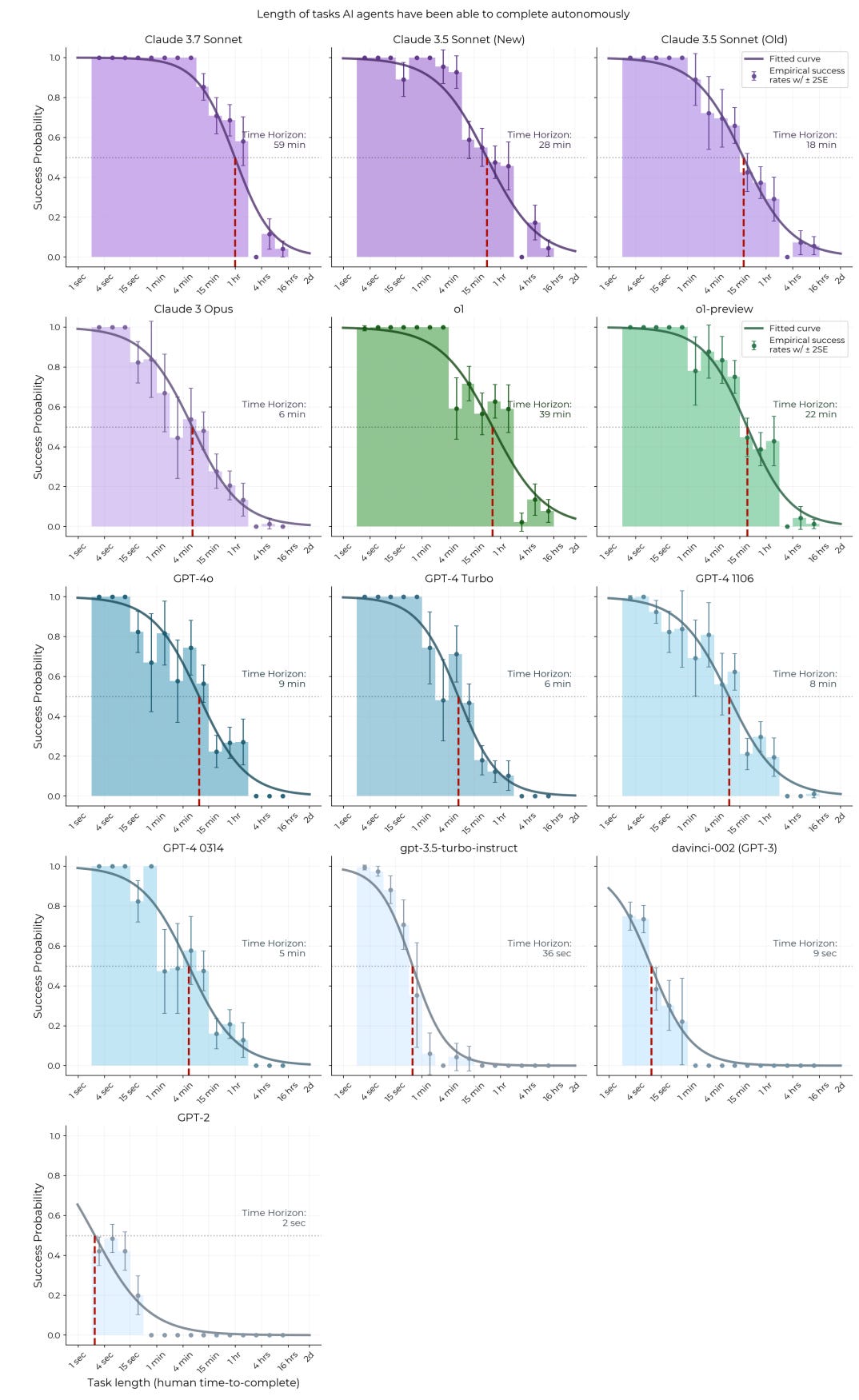

Andrey: You might—that's fair. Okay, so the second claim is: the different models have very different patterns of either substituting away from existing models or expanding the market. And I think two models that really highlight that are Claude 3.7 Sonnet, which primarily cannibalizes from Claude 3.5 Sonnet.

Seth: New Coke,

Andrey: Yes, and it's—well, New Coke failed in this regard.

Seth: Diet Coke,

Andrey: Yeah. And then another model is Google's Gemini 2.0 Flash, which really expanded the market on this platform. A lot of people started using it a lot and didn't seem to have noticeable effects on other model usage.

Seth: Right?

Andrey: So this is kind of showing that kind of models are competing in this interesting space.

Seth: My gosh. Andrey, do you want me to evaluate the claim that you made, or are you now just vaguely appealing to competition? Which of the two do you want me to put a prior on?

Andrey: No no no. Go for it. Yeah.

Seth: All right, so the first one is: do I think that if I look at, you know, a website with a hundred different models, some of them will steal from the same company and some of them will lead to new customers?

Right? I mean with a—I, I'm a little bit… Suppose we asked this question about products and you said, “Professor Benzel, will my product steal from other demands, or will it lead to new customers?” I guess at a certain level, it doesn't even make sense, right? There's a general equilibrium problem here where you always have to draw from something else.

I know we're drawing from other AIs, which would mean that there would have to be some kind of substitution. So I mean, yes, I believe sometimes there's going to be substitution, and yes, I believe sometimes, for reasons that are not necessarily directly connected to the AI model, the rollout of a new model might bring new people into the market.

Right. So I guess I agree. Like at the empirical level, I would say 95% certain that models differ in whether they steal from other models or bring in new people. If you're telling me now there's like a subtler claim here, which is that the fact that some models bring in new people is suggestive of horizontal differentiation and is further evidence for strong horizontal differentiation.

And I'm a little bit, I don't know, I'll put a probability on that, but that's, that seems to be go