Can a Nation Survive on Charity?

Description

Act 1. Andrew Carnegie

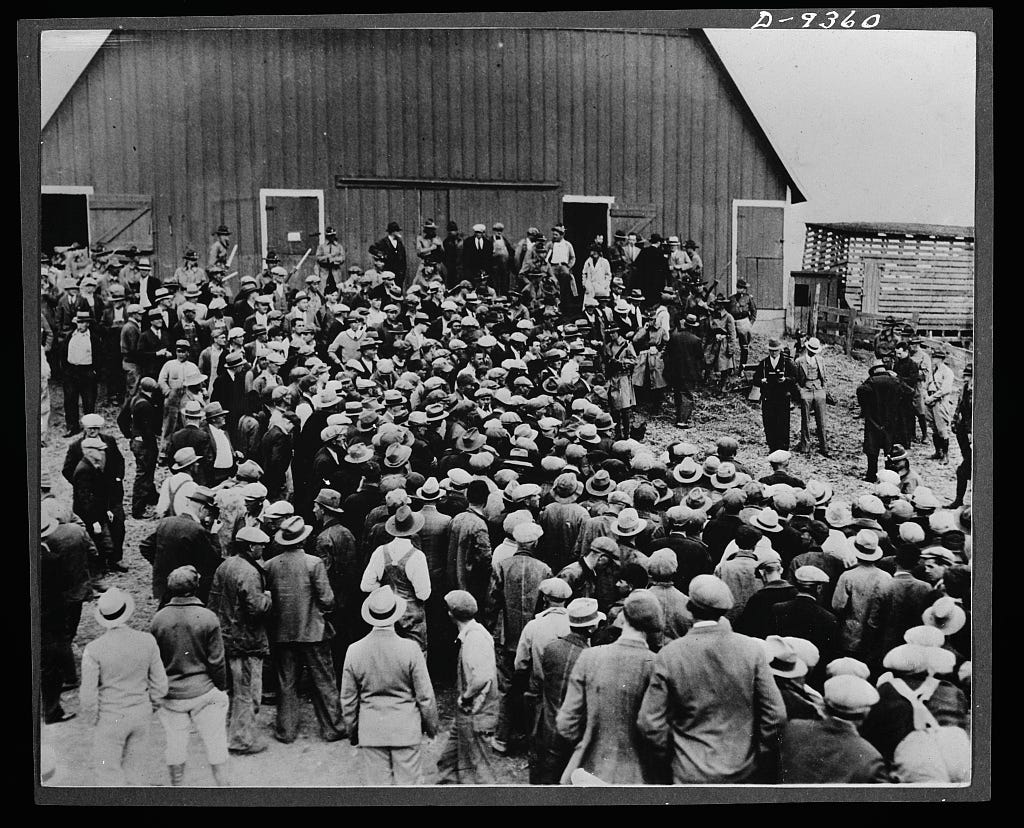

It’s 1892. Homestead, Pennsylvania.

Andrew Carnegie pays his steelworkers an average of $1.68 a day. About $56 in today’s money. Twelve-hour shifts. Six days a week.

The workers and their families shared rooms that smelled like smoke and steel dust. The beds were never cold because workers on different shifts all used them. They ate bread, onions, sometimes meat. The lucky ones had shoes that fit. Nutrition, sanitation, and health were poor. Workplace injuries were common.

Meanwhile, Carnegie’s personal annual income in 1892 was approximately $25 million. That’s $830 million in today’s dollars. Per year.

Here’s a simple question: Why didn’t he just pay the workers more?

Not out of charity or kindness. Just pay them enough that they didn’t have to send their children to work at age ten. Pay them enough that they could afford doctors when they got injured. Pay them enough that their widows didn’t end up in poorhouses.

Carnegie’s answer, laid out in his 1889 essay The Gospel of Wealth, was surprisingly direct.

He argued that giving workers higher wages would be wasteful. Most workers lacked the judgment to use extra money wisely. They’d spend it on alcohol, gambling, and frivolous consumption. He wrote, “It were better for mankind that the millions of the rich were thrown into the sea than spent to encourage the slothful, the drunken, the unworthy.”

Better, Carnegie said, to keep wages low, accumulate wealth, and then give it away strategically. To libraries or universities. Institutions that would uplift the deserving poor, not reward the undeserving.

Were his workers not deserving? But in the case of Carnegie, it was also something deeper. A theory about the nature of giving. About the difference between waste and virtue.

Let’s test the logic.

In 1892, Carnegie Steel employed about 40,000 workers across all operations. If Carnegie had taken just $5 million of his $25 million annual income and distributed it evenly among those workers, each one would have received an extra $125 per year, about $4300 today.

That’s not life-changing money. But it’s enough to buy winter coats for your kids. Enough to see a doctor instead of dying from an infected cut. Enough to not send your twelve-year-old to work in the mill.

But Carnegie didn’t do that.

Instead, over his lifetime, he gave away $350 million to build libraries, concert halls, and universities. He gave 2,811 libraries to communities.

So here’s the next question: Why did he consider the second option virtuous, but the first wasteful?

A worker who needs $2 a day to feed his family needs it whether you hand it to him on Friday or donate it to a library that his grandchildren might use.

We all need heat in the house and food on the table. The need doesn’t change. Only the giver’s relationship to it does.

There’s an old idea, older than Carnegie, older than America, that we owe two kinds of debts. Give to Ceasar what is Ceasar’s, and to God what is God’s.

First, our debt to Ceasar. This debt is civic. What we owe to the state, to the community, to the infrastructure that makes our lives possible. Roads, courts, defense, clean water. We pool our resources to build what none of us can build alone.

The other debt is moral. What we owe to each other as human beings. Compassion, dignity, the recognition that suffering is real and we have some responsibility to ease it.

The civic debt is the price of civilization. We choose to escape chaos. We pay taxes because without a functioning state, there is no property to protect, no contracts to enforce, no prosperity to enjoy.

The moral debt is civic friendship, the sense that we share a common life and therefore share some responsibility for each other’s welfare. Our neighbors. Communities. Churches.

For most of human history, these debts lived in separate accounts.

We paid taxes to keep the state running. We gave alms to benefit those around us in our communities.

One was mandatory. One was voluntary. One was civic duty. One was personal virtue. They didn’t compete with each other.

But then something changed.

By the late 1800s, charity wasn’t just feeding a beggar on the street corner anymore. It was building hospitals. Funding schools. Running orphanages. Feeding entire cities during economic panics.

And government wasn’t just maintaining roads anymore. A series of economic depressions and rapid industrial revolution brought a dramatic increase in individual and community needs. People started to ask: What if the state could do what charity does, but bigger, more reliably, for everyone?

Suddenly, the two debts started to overlap. State duty, and civic duty, blended together. Blending the two brought philosophical questions.

If the government funds hospitals through taxes, do we still need to donate to hospitals?

If the state provides old-age pensions, does that make personal charity for the elderly obsolete?

If the government takes care of the poor through mandatory taxes, does that rob us of the opportunity to be virtuous?

There’s an argument that an act is only morally praiseworthy if it’s done freely, out of genuine choice, not out of compulsion. That we should voluntarily give in secret. By that logic, paying taxes to fund welfare isn’t a moral act. It’s just compliance.

But choosing to donate to a soup kitchen is virtue. Proof of your moral character.

Carnegie never framed it in philosophical terms, but his entire worldview rested on keeping those two debts separate.

The civic debt, what we owe the state, should be minimal. Low taxes, limited government, just enough to keep order and protect property.

The moral debt, what we owe our fellow man, should be voluntary, personal, strategic. We give when and how we see fit. And most importantly: the moral debt is where virtue lives.

But there’s a problem with this framework: it only works if we assume that our wealth is our own to begin with.

What if our wealth is civic obligation? What if the wages we don’t pay, the safety equipment we don’t buy, the unions we crush, weren’t private business decisions? What if they are civic failures?

Then our philanthropy isn’t generosity. We are just hurting our neighbors in the name of virtue.

Americans donate about $500 billion to charity every year. That’s 2% of GDP.

Meanwhile, we spend about $3.7 trillion on what we call government social programs. These are programs like Social Security, Medicaid, SNAP, and housing assistance. That’s roughly 12% of GDP.

Americans prefer smaller government and lower taxes, but at the same time support programs like Social Security and Medicare. So the tension isn’t really about whether government should help people, but about how we want to frame that help, and whether we get credit for it.

It’s not because charity is more efficient. Government programs have competitive or lower costs than private charities. Medicare’s administrative costs are competitive or better than private health insurance overhead at 12-18%.

It’s not because charity reaches more people. SNAP alone feeds 42 million Americans. Feeding America’s charity network serves about 50 million people annually, including 12 million children and 7 million seniors. One program doesn’t dwarf the other.

So is charity better? Some are convinced that only voluntary giving counts as virtue. Paying taxes, even if that money feeds hungry children, is obligation. Donating to a food bank is morality.

Same outcome. Different emotional accounting.

There’s research on this from <a href="https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3920088/#:~:text=The%20Gift%20Relationship%20(1970)%20by,decrease%20if%20incentives%20were%20introduced." target="_blank"