The House You'll Never Own

Description

Act One. The Penny Auctions

Nebraska, October 6, 1932. Five and a half miles southwest of Elgin, in the middle of farm country. Theresa Von Baum, a widow who worked her 80-acre farm with only the help of her sons after her husband’s death, couldn’t make the payment on her $442 mortgage. The bank moved to foreclose.

The bank expected to make hundreds, or even thousands, of dollars for the farm.

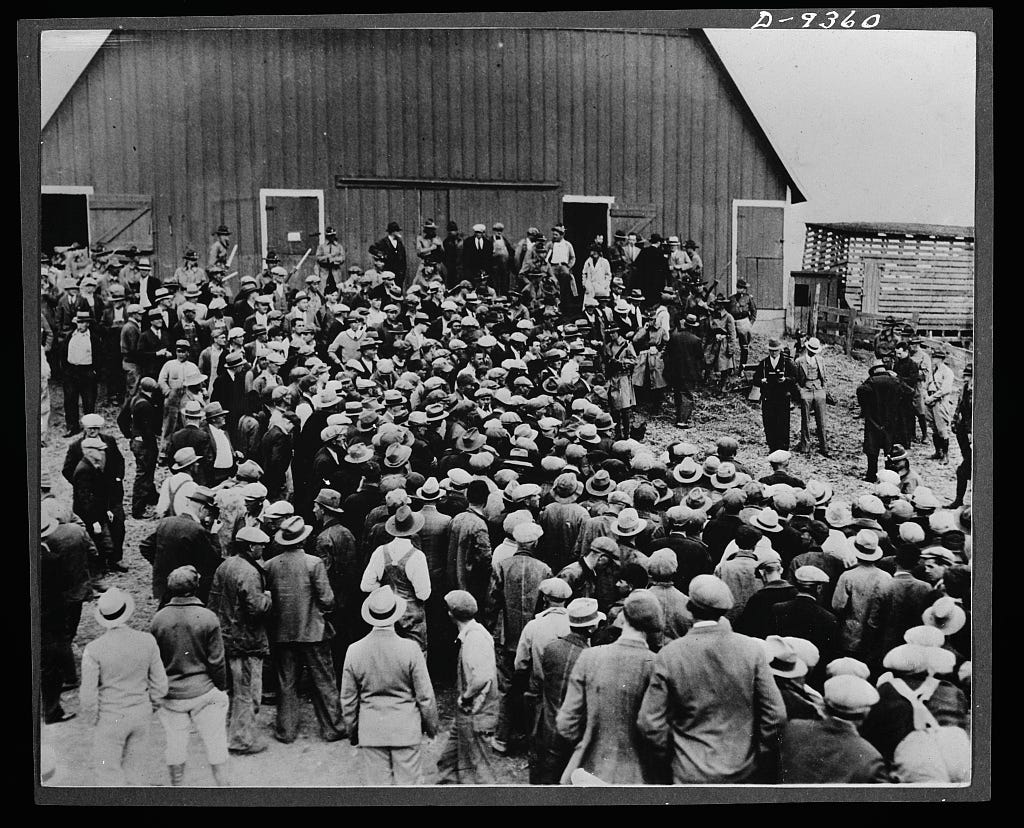

Nearly 3,000 farmers from Antelope and neighboring counties showed up at the Von Baum farm that day. They stood in silence. Waiting.

The receiver, the bank’s man, wanted to reschedule. The farmers didn’t move. After some back and forth, the receiver finally backed down. The auction would proceed.

The auctioneer started. Cows went for 35 cents apiece. Six horses sold for a total of $5.60. Plows, a hay binder, and a corn planter all brought just a few cents.

Harvey Pickrel remembered it later: “Some of the farmers wouldn’t bid on anything at all - because they were trying to help the man that was being sold out.”

When it was over, the farmers passed the hat among themselves. The total came to $101.02. They immediately returned the animals and equipment to Theresa Von Baum. Then the farmers handed the money to the receiver. He looked at the crowd. Probably counted heads. Probably decided that forcing the issue wasn’t likely to get him a cent more, and might get him a broken nose, or worse. He accepted the money as payment in full for the mortgage, got in his car, and drove back to town.

People called them “penny auctions.” Others called them “Sears Roebuck sales,” because a penny was what you paid for something in a catalog. A joke price.

This wasn’t for just one widow in Nebraska.

In 1931, about 150 farmers showed up at another foreclosure auction, the Von Bonn family farm in Madison County, Nebraska. The first bid was five cents. When someone else tried to raise it, he was forcibly requested not to do so. Item after item got only one or two bids. The total proceeds were $5.35. The farmers expected the bank to accept this sum to pay off the loan.

In Wood County, Ohio, on January 26, 1933, some 700 to 800 farmers stood out in the cold at Wally Kramp’s farm. Kramp owed $800 on a loan he couldn’t repay. He’d been hospitalized with appendicitis, and crop prices had collapsed. The farmers bid pennies on each item, then returned everything to Kramp on a 99-year lease. They passed the hat. Even the auctioneers donated their take from the sale.

In some places, farmers threatened outsiders who might think about bidding with physical harm and death threats. These were not empty threats.

This was happening all over the Midwest. There were maybe a dozen auctions a day in early 1933. Iowa, Nebraska, Wisconsin, Minnesota. Farmers who had paid their mortgages for ten, fifteen, twenty years, never missed a payment, were losing everything.

The banks had structured the loans to fail when credit dried up.

Before the 1930s, most mortgages in America were five to ten years, interest-only, with a huge balloon payment at the end. You paid the bank for years. Then you had to refinance the whole thing all at once. If you couldn’t roll it over, the bank took the farm. Or the house.

When the economy crashed in 1929, banks stopped lending. In 1932, 273,000 people lost their homes to foreclosure. By 1933, banks foreclosed on more than 200,000 farms. Between 1930 and 1935, farmers lost a third of all American farms.

Some communities didn’t take it quietly. It wouldn’t be the first time that farmers threatened nobles, even if they didn’t use pitchforks.

And it wouldn’t be the last.

Le Mars, Iowa. April 27, 1933. A Thursday afternoon. Judge Charles Clark Bradley, 54 years old, a bachelor with fifteen years on the bench, looked up from his desk at a rowdy crew shoving their way into his small courtroom.

Some were farmers in ragged overalls. Others looked like ruffians from nearby Sioux City. They kept their hats on. Kept smoking.

They’d come to demand that Judge Bradley suspend foreclosure proceedings until recently passed state laws could be considered. One farmer remarked that the courtroom wasn’t Bradley’s alone. Farmers had paid for it with their taxes.

Judge Bradley refused. He said, “Take off your hats and stop smoking in my court room.”

Next thing he knew, dozens of rough hands were mauling him. They yanked him off his bench and dragged him out to the courthouse lawn.

“Will you swear you won’t sign no more mortgage foreclosures?” demanded a man with a blue bandana across his face.

Judge Bradley’s quiet answer: “I can’t promise any such thing.”

Someone struck him in the mouth. “Will you swear now?” The jurist toppled to his knees. His teeth felt loose but he managed to reply: “No, I won’t swear.”

A truck rattled up. The men threw Judge Bradley into it. His kidnappers tied a dirty handkerchief across his eyes. The truck drove a mile out of town and stopped at a lonely crossroads.

Again they asked the judge to sign no more foreclosures. Again he refused. They slapped and kicked, knocked him to the ground, and jerked him back to his feet. They tied a rope around his neck, the other end thrown over a roadside sign. They tightened the rope. Judge Bradley wheezed, thought they were killing him.

“Now will you swear to sign no more foreclosure orders?” A man unscrewed a greasy hubcap from the truck and placed it on his head.

Judge Bradley looked at them and said, “I will do the fair thing to all men to the best of my knowledge.”

They pulled the noose tight. Just in time, a local newspaper editor arrived in his car and intervened.

Judge Bradley refused to identify his assailants or press charges.

Iowa Governor Clyde Herring called the attack “a vicious and criminal conspiracy and assault upon a judge while in the discharge of his official duties, endangering his life and threatening a complete breakdown of law and order.” He declared martial law in Plymouth County. He sent in three National Guard companies from Sioux City and a fourth from Sheldon.

The case made the front page of the New York Times.

Twelve days later, Governor Herring lifted martial law. Seven men were eventually tried for the attempted lynching. They got sentences ranging from one to six months.

The penny auctions effectively forced the banks to release the property without an opportunity to be paid the balance of the loan. If the pennies didn’t clear the bank debt, the farmers physically threatened the bank officers. So legally, the farmer still owed. But practically, the system had broken down.

With the beginning of Roosevelt’s presidency in 1933, creditors and debtors began to work together to refinance and resolve payment of delinquent debts.

Between 1933 and 1935, twenty-five states passed farm foreclosure moratorium laws that temporarily prevented banks from foreclosing. The Federal Farm Bankruptcy Act of 1934 aimed to provide farmers with the opportunity to regain their land even after foreclosure.

The penny auctions didn’t erase the debt. But they made normal foreclosure impossible. They created chaos. Mobs dragging judges out of courtrooms. Nooses at farm auctions. Armed farmers blocking highways. This chaos threatened domestic tranquility.

That’s one of our six nationa