When Humans and Machines Don't Say What They Think

Description

Andrey and Seth examine two papers exploring how both humans and AI systems don't always say what they think. They discuss Luca Braghieri's study on political correctness among UC San Diego students, which finds surprisingly small differences (0.1-0.2 standard deviations) between what students report privately versus publicly on hot-button issues. We then pivot to Anthropic's research showing that AI models can produce chain-of-thought reasoning that doesn't reflect their actual decision-making process. Throughout, we grapple with fundamental questions about truth, social conformity, and whether any intelligent system can fully understand or honestly represent its own thinking.

Timestamps (Transcript below the fold):

1. (00:00 ) Intro

2. (02:35 ) What Is Preference Falsification & Why It Matters

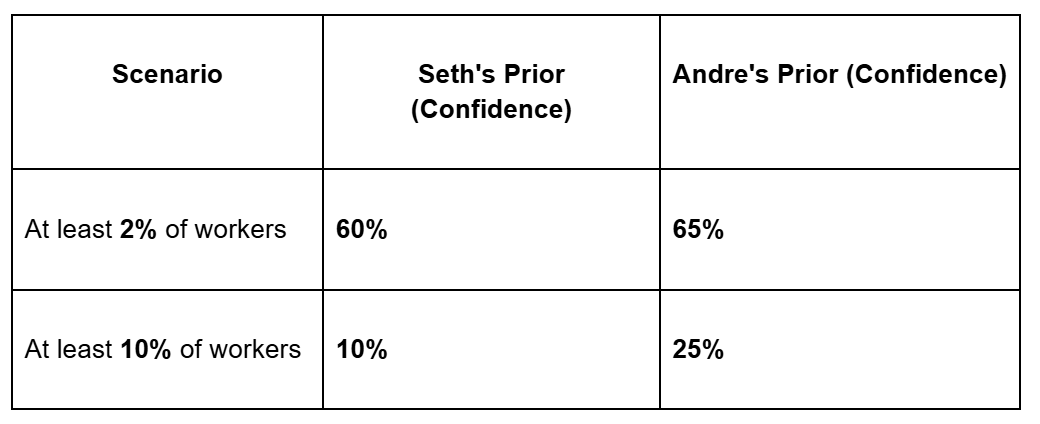

3. (09:38 ) Laying out our Priors about Lying

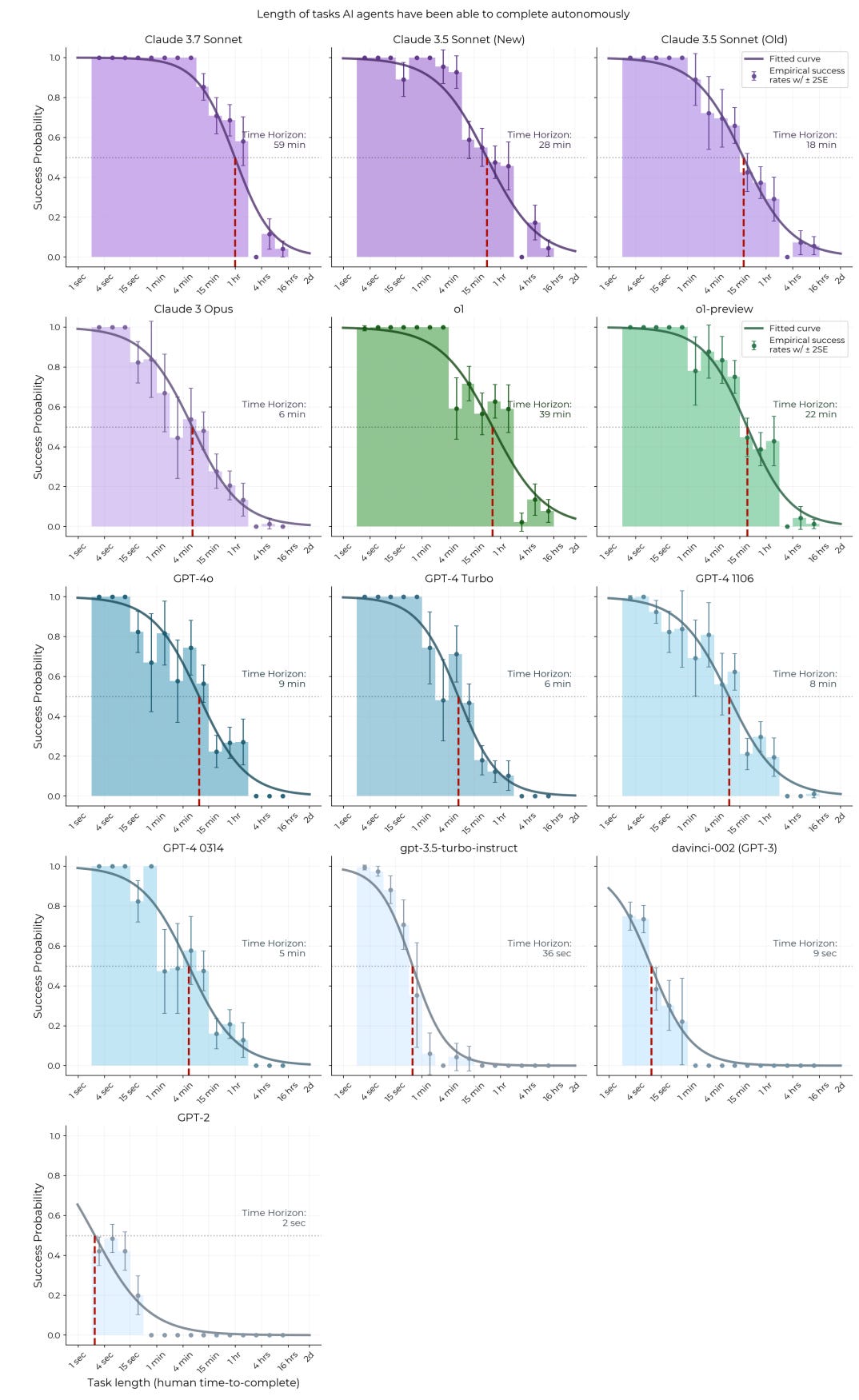

4. (16:10 ) AI and Lying: “Reasoning Models” Paper

5. (20:18 ) Study Design: Public vs Private Expression

6. (24:39 ) Not Quite Lying: Subtle Shifts in Stated Beliefs

7. (38:55 ) Meta-Critique: What Are We Really Measuring?

8. (43:35 ) Philosophical Dive: What Is a Belief, Really?

9. (1:01:40 ) Intelligence, Lying & Transparency

10. (1:03:57 ) Social Media & Performative Excitement

11. (1:06:38 ) Did our Views Change? Explaining our Posteriors

12. (1:09:13 ) Outro: Liking This Podcast Might Win You a Nobel Prize

Research Mentioned:Political Correctness, Social Image, and Information Transmission

Reasoning models don’t always say what they think

Private Truths, Public Lies: The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification

🗞️Subscribe for upcoming episodes, post-podcast notes, and Andrey’s posts:

💻 Follow us on Twitter:

@AndreyFradkin https://x.com/andreyfradkin?lang=en

@SBenzell https://x.com/sbenzell?lang=enTRANSCRIPT

Preference Falsification

Seth: Welcome to the Justified Posteriors podcast—the podcast that updates beliefs about the economics of AI and technology. I'm Seth Benzel, unable to communicate any information beyond the blandest and most generic platitudes, coming to you from Chapman University in sunny Southern California.

Andrey: And I am Andrey Fradkin, having no gap between what I say to the broader public and what I think in the confines of my own mind. Coming to you from Irvington, New York—in a castle.

Seth: On the move.

Andrey: Yes. This is a mobile podcast, listeners.

Seth: From a castle. So, I mean, are you tweaking what you're saying to conform to the castle's social influence?

Andrey: Well, you see, this is a castle used for meditation retreats, and so I'll do my best to channel the insights of the Buddha in our conversation.

Seth: Okay. All right. Doesn't the Buddha have some stuff to say about what you should and shouldn’t say?

Andrey: Right Speech, Seth. Right Speech. That means you should never lie.

Seth: Wait.

Andrey: Is it?

Seth: True speech. Why doesn't he just say “true speech” then?

Andrey: Well, look, I'm not an expert in Pali translations of the sacred sutras, so we’ll have to leave that for another episode—perhaps a different podcast altogether, Seth.

Seth: Yes. We might not know what the Buddha thinks about preference falsification, but we have learned a lot about what the American Economic Review, as well as the students at UCSD and across the UC system, think about preference falsification. Because today, our podcast is about a paper titled Political Correctness, Social Image, and Information Transmission by Luca Braghieri from the University of Bocconi.

And yeah, we learn a lot about US college students lying about their beliefs. Who would’ve ever thought they are not the most honest people in the universe?

Andrey: Wow, Seth. That is such a flippant dismissal of this fascinating set of questions. I want to start off just stating the broad area that we’re trying to address with the social science research—before we get into our priors, if that’s okay.

Seth: All right. Some context.

Andrey: Yes. I think it’s well known that when people speak, they are concerned about their social image—namely, how the people hearing what they say are going to perceive them. And because of this, you might expect they don’t always say what they think.

And we know that’s true, right? But it is a tremendously important phenomenon, especially for politics and many other domains.

So politically, there’s this famous concept of preference falsification—to which we’ve already alluded many times. In political systems, particularly dictatorships, everyone might dislike the regime but publicly state that they love it. In these situations, you can have social systems that are quite fragile.

This ties into the work of Timur Kuran. But even outside of dictatorships, as recent changes in public sentiment towards political parties and discourse online have shown, people—depending on what they think is acceptable—might say very different things in public.

And so, this is obviously a phenomenon worth studying, right? And to add a little twist—a little spice—there’s this question of: alright, let’s say we’re all lying to each other all the time. Like, I make a compliment about Seth’s headphones, about how beautiful they are—

Seth: Oh!

Andrey: And he should rationally know I’m just flattering him, right? And therefore, why is this effective in the first place? If everyone knows that everyone is lying, can’t everyone use their Bayesian reasoning to figure out what everyone really thinks?

That’s the twist that’s very interesting.

Seth: Right. So, there’s both the question of: do people lie? And then the question of: do people lie in a way that blocks the transmission of information? And then you move on to all the social consequences.

Let me just take a step back before we start talking about people lying in the political domain. We both have an economics background. One of the very first things they teach you studying economics is: revealed preferences are better than stated preferences.

People will say anything—you should study what they do, right? So, there’s a sense in which the whole premise of doing economic research is just premised on the idea that you can’t just ask people what they think.

So, we’ll get into our priors in one moment. But in some ways, this paper sets up a very low bar for itself in terms of what it says it’s trying to prove. And maybe it says actually more interesting things than what it claims—perhaps even its preferences are falsified.

Andrey: Now we’re getting meta, Seth. So, I’d push back a little bit on this. That’s totally correct in that when people act, we think that conveys their preferences better than when they speak.

But here, we’re specifically studying what people say. Just because we know people don’t always say what they really want or think doesn’t mean it’s not worth studying the difference between what they think and what they say.

Seth: Well, now that you’ve framed it that way, I’ll tell you the truth.

Andrey: All right. So let’s get to kind of the broad claim. I don’t think we should discuss it too much, but I’ll state it because it’s in the abstract.

The broad claim is: social image concerns drive a wedge between sensitive sociopolitical attitudes that college students report in private versus in public.

Seth: It is almost definitionally true.

Andrey: Yeah. And the public ones are less informative.

Seth: That’s the...

Andrey: And then the third claim, maybe a little harder to know ex ante, is: information loss is exacerbated by partial audience naivete—

Seth: —meaning people can’t Bayesian-induce back to the original belief based on the public utterance?

Andrey: Yes, they don’t.

Seth: Rather, whether or not they could, they don’t.

Andrey: Yes, they don’t.

Seth: Before we move on from these—in my opinion—either definitionally correct and therefore not worth studying, or so context-dependent that it’s unreasonable to ask the question this way, let me point out one sentence from the introduction: “People may feel social pressure to publicly espouse views… but there is little direct evidence.” That sentence reads like it was written by someone profoundly autistic.

Andrey: I thought you were going to say, “Only an economist could write this.”

Seth: Well, that’s basically a tautology.

Andrey: True. We are economists, and we’re not fully on the spectrum, right?

Seth: “Fully” is doing a lot of work there.

Andrey: [laughs] Okay, with that in mind—

Seth: Sometimes people lie about things.

Andrey: We all agree on that.