Reward Work, Build Opportunity

Description

Last week, David Leonhardt, writing for the New York Times, questioned whether any of President Biden’s legacy would endure. Most Americans view his term unfavorably. Parties with one-term presidents often see those presidencies as failures and shift their focus to the future. However, Leonhardt highlighted one aspect of Biden’s agenda that may leave a lasting mark. This is the idea that “the federal government should take a more active role in both assisting and regulating the private sector than it did for much of the previous half-century.”

President Biden is not alone in his assessment. Both parties agree to some extent that unfettered free market globalization is not in America’s best interest. Similar to an approach used in the Gilded Age, President Trump intends to influence the global economic system through tariffs.

In his farewell address from the Oval Office, President Biden said, “Today, an oligarchy is taking shape in America of extreme wealth, power, and influence that literally threatens our entire democracy…We’ve seen it before, more than a century ago, but the American people stood up to the robber barons back then.”

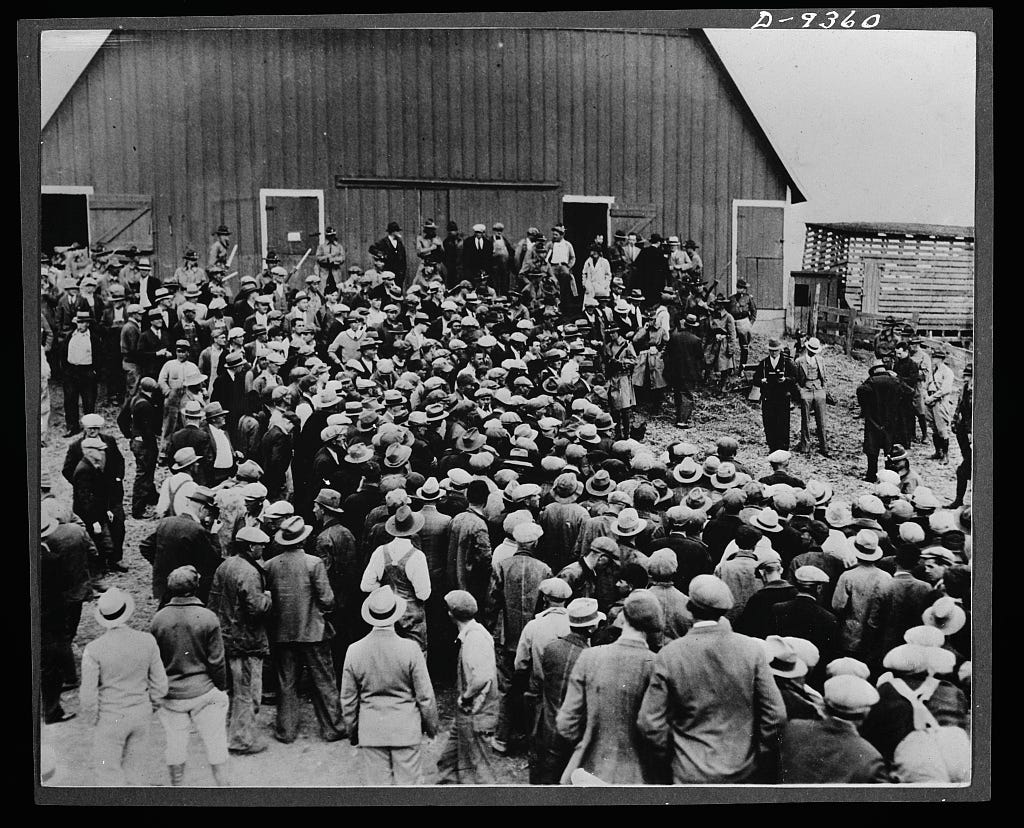

Biden’s use of the term ‘robber barons’ is a reference to a phrase from the late 19th century, when Mark Twain’s The Gilded Age gave that period its name. From the 1870s to the early 1900s, the Gilded Age saw rapid industrialization, economic growth, glaring inequality, and societal transformation. It was also a time of innovation. From the birth of America to 1870, the US Patent Office granted 40,000 patents. By 1900, that number exploded tenfold. The country’s population nearly doubled in those 30 years from immigrants flooding into the nation to work in the factories. During this era, industrial magnates like Rockefeller, Carnegie, Vanderbilt, and Stanford amassed immense wealth. Twain satirized their greed and the corruption that defined America’s elite.

As the country experiences rapid digital transformation and robust economic growth, parallels to the Gilded Age are hard to ignore. Unlike then, wealth is concentrated in corporations rather than individuals and families. Like in the Gilded Age, many American families are left behind. Inefficient social programs that did not exist in the Gilded Age prop up society, but these programs come at the cost of unprecedented national debt. Without them, unrest would mirror the turmoil of the Gilded Age.

Leonhardt observed that the emerging idea of a more active federal role in regulating the private sector still lacks a name. Scholars and policymakers have referred to it as the “end of the neoliberal order,” “a new economics,” or “a new centrism.”

He makes a strong point. America has faced at least two significant periods of inequality before. In both instances, unifying messages helped Americans rise to the challenge. But before considering names, it’s worth breaking this idea into two fundamental questions.

First, do Americans have a mandate to address inequality?

Second, if Americans have a mandate and decide to act, what simple message could unite the nation and drive change?

Let’s start by considering the first question. Should Americans choose to address inequality?

Should America Address Inequality?

Businesses have no responsibility to address social inequality. None. Businesses have responsibilities only to their business and their shareholders. Diverting effort away from generating profit is using someone else’s money—shareholders, employees, or customers—for purposes they did not agree to. A business’s primary responsibility is to increase profits, and corporate executives should focus solely on maximizing shareholder value within legal and ethical boundaries. Any effort toward social justice is outside a business’s fundamental responsibility unless it directly contributes to profitability. While some businesses voluntarily pursue social initiatives, their fundamental legal responsibility is to maximize shareholder value.

Therefore, arguments claiming that businesses should pay higher wages to address social inequality are flawed, as businesses have no inherent responsibility to resolve societal issues. Declaring that an individual or group ‘should’ do something for which they have no responsibility (and therefore, no requirement) means they will do exactly what they are required to do. In this case, exactly nothing.

So…if businesses are not responsible for paying livable wages and can find workers willing to accept poverty-level pay, they have little incentive to raise wages voluntarily.

To continue this argument, we need to note that Americans can earn money from two sources: their work, or their fellow taxpayers in the form of the government. Because Americans get money from both sources, this leaves the government to address the shortfall in wages.

Through social programs, Congress spends the American people’s money to support society as a result of low wages. These social programs, subsidies, and incentives are supported by taxes collected from the American people. And our elected representatives certainly have the requirement to spend taxpayer money responsibly.

The basis of this requirement is found in Constitutional provisions that include the Spending Clause (Article I, Section 8), which directs Congress to allocate funds for defense and general welfare. It is further found in the Appropriations Clause (Article I, Section 9, Clause 7), which mandates transparency and accountability in public expenditures. Additionally, federal laws like the Antideficiency Act prohibit spending beyond appropriations, underscoring the Congressional duty to ensure fiscal discipline.

There’s another fascinating wrinkle here.

In United States v. Butler (1936), the Supreme Court ruled that Congress has the authority to spend money for the “general welfare” under the Spending Clause but that the Constitution limits that authority. This spending must serve the common good, not specific groups or industries. Subsidizing low wages with public funds serves business interests but not the American people as a whole.

Spending on social programs to help those who aren’t able to work supports American society by promoting order and tranquility. But half of American working families needing social program support is wildly excessive and points to low wages as a root cause problem.

The burden of wages has shifted from employers to taxpayers, violating the principle that public spending should benefit the nation as a whole.

We, the People, must meet the Constitutional standard to promote the general welfare. Therefore, Congress must act to reduce reliance on social programs by addressing systemic wage issues. Failure to do so violates Constitutional principles and harms the American public.

…

In short, we can answer our first question.

Do Americans have a mandate to address inequality?

Yes, Americans and our elected representatives have a Constitutional and legal mandate to address inequality. Failure to minimize spending on taxpayer-funded social programs benefits only special business interests, not the American people as a whole. This violates the Constitution. Therefore, we are mandated to take an active federal role in regulating the private sector.

Now, let’s recall our second question.

If Americans have a mandate and decide to act, what simple message could unite the nation and drive change?

History shows that when America faced inequality in the past, it found its way through unity and purpose. To understand how this was achieved, let’s turn to our nation’s first period of radical inequality and the leadership of Abraham Lincoln.

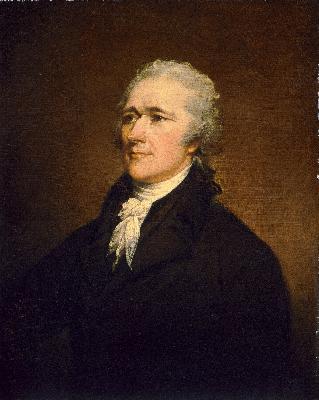

Lincoln’s Legacy

Abraham Lincoln led the nation through its first great reckoning with radical inequality. The divide between free labor in the North and enslaved labor in the South symbolized a moral and economic conflict. <