Why Is Remembering American History So Hard?

Description

Why is remembering American history so hard? It’s a question that needs an answer because Black history is American history, and federal agencies decided to ban Black History Month.

Black history isn’t just Black history. It’s a record of our constant battle between order and justice. To erase it is to erase the struggle that defines our national identity. It may be easier to maintain a neat, sanitized version of our history than to confront the struggle and resistance justice demands, but that ease is detrimental to America.

If remembering Black history is too difficult, maybe we should turn to the one document that defines our national values. Every state in the Union agreed with the verbiage. You’d think it would offer clarity.

But even there, justice and order are locked in a constant struggle. The Constitution sets both as national goals, side by side. Then, history demonstrates again and again how the ideals clash and how essential they are to each other.

Justice Disrupts Order, and Order Suppresses Justice

Last week, we discussed the inherent tension between justice and order. Ensuring domestic tranquility and establishing justice are two of our six national goals, but they are often at odds.

Tranquility means a society built on order, stability, and mutual respect. Tranquility is a deliberate national choice to maintain a collective structure.

Justice is the foundation for a society in which individuals can fulfill their roles and contribute to the nation’s well-being. It includes fair and equal treatment under the law, equal access to individual opportunity, and equitable distribution of resources like education, healthcare, and housing.

Justice threatens order. We build institutions and cultural norms around systems that offer stability but perpetuate inequality and power imbalance. Calls for justice expose inherent flaws. They challenge the status quo.

Order threatens justice. While order is necessary for social stability, the rigid pursuit of order obstructs justice. Groups in power preserve the status quo instead of addressing systemic imbalances. They argue that stability must be maintained at all costs. This focus on order suppresses dissent and marginalizes groups that call for reform.

No American better embodies the tension between justice and order than the great Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

But to really understand the challenge of justice, order, and Dr. King, we need to first understand Reverend Billy Graham.

Billy Graham Believed in Order

In 1954, TIME Magazine called Reverend Billy Graham “the best-known, most talked-about Christian leader in the world today, barring the Pope.” US presidents sought his council. He became the moral advisor to the nation.

By 1957, Graham was at the height of his influence as America’s most prominent evangelist. That year marked his landmark New York City Crusade. The 16-week revival held at Madison Square Garden drew massive crowds. Over two million people attended, and more than 60,000 responded to his call for conversion.

Graham’s sermons emphasized personal salvation and moral living. His message resonated with many Americans wrestling with Cold War anxiety and social change. It offered comfort in uncertain times.

During this crusade, Graham crossed paths with a young reverend, Martin Luther King Jr., for the first time. Graham hoped to expand the reach of his message to a broader audience and invited King to speak in New York. King spoke of a brotherhood that transcended race and color. He hoped alliances with influential figures like Graham could accelerate the fight for civil rights.

By 1960, differences between the two men’s approaches emerged. Graham made it clear he valued social order above civil disobedience. He stated…

“I do believe that we have a responsibility to obey the law. Otherwise, you have anarchy. And, no matter what that law may be—it may be an unjust law—I believe we have a Christian responsibility to obey it.”

There it is. Order versus justice.

Graham wasn’t just preaching personal salvation—he was tapping into a national desire for stability in a time of upheaval. For many, his message was a soothing alternative to the discomfort of systemic injustice.

Graham’s stance reflected the views of many Americans at the time. They were uncomfortable with the confrontational approach of the Civil Rights movement. They preferred order to justice. Graham’s supporters argue he wasn’t racist. They argue he was called to a mission focused on personal salvation rather than political activism. His critics argue that his reluctance to challenge unjust laws reflected a failure to meet the moral urgency of the moment.

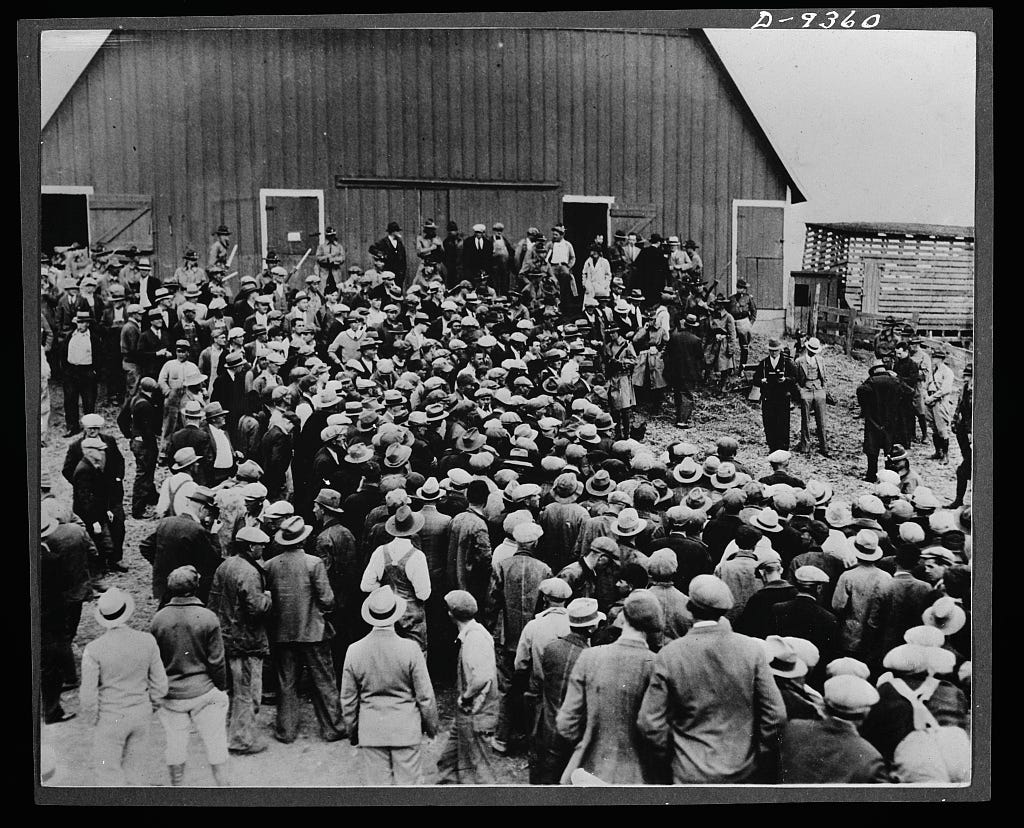

No matter the reason, his line was drawn by April 1963. As Graham envisioned order, King led the Birmingham Campaign. This bold, nonviolent movement targeted deep-rooted segregation and racial injustice in one of America’s most racially divided cities.

Letter from a Birmingham Jail

In April 1963, Birmingham, Alabama, was the most violently racist city in the United States. Its aggressive resistance to desegregation earned it the nickname “Bombingham” due to the frequent bombings of Black homes and churches by white supremacists. From 1945 to 1962, white supremacists conducted 50 racially motivated bombings of Black American homes, businesses, and churches.

They bombed the home of Reverend Milton Curry Jr. on August 2, 1949. The home of Monroe and Mary Means Monk on December 21, 1950. The home of the minister of Bethel Baptist Church, Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, on December 24, 1956. The Ku Klux Klan bombed Bethel Baptist Church on June 29, 1958. It was the second time the Klan had bombed the church.

On and on. 50 bombings.

Amid the years of bombings, Public Safety Commissioner Bull Connor led the city government to openly enforce Jim Crow laws with brutal tactics. They used police dogs, fire hoses, and mass arrests to suppress civil rights demonstrations.

Quite a backdrop.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. arrived in Birmingham, Alabama, on April 3, 1963, to lead the Birmingham Campaign. It was the season of the major Christian holiday of Easter. On Easter, Christians celebrate the resurrection of Jesus Christ and his love for humanity. We remember our vow to love God and love others.

King’s Birmingham Campaign included nonviolent protests against segregation and racial injustice. King and other activists planned sit-ins, marches, and boycotts targeting businesses that upheld segregation.

On April 10, 1963, Circuit Judge of the Tenth Judicial Circuit of Alabama W. A. Jenkins, Jr. issued an injunction prohibiting the demonstrations.

King and others chose to defy the order. They viewed it as an unjust law meant to suppress their Constitutional rights. On April 12, Good Friday, the day Christians remember the Romans putting Christ to death, authorities arrested King and at least 55 other leaders for “parading without a permit.” <a href="https://news.ua.edu/2022/02/piece-of-history-mlk-letter-from-birmingham-jail-at-special-collections/#:~:text=It%20was%201963%20and%20the,the%