Why do we need more H-1B Visas?

Description

H-1B visas have been an item of hot discussion lately. On New Year’s Day, Newsweek detailed, “At the end of December a bitter row broke out within Trump’s MAGA (Make America Great Again) movement over H-1B visas, pitting business figures such as Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy who believe they boost the U.S. economy against more nativist elements who think they harm American workers. And, speaking to The New York Post on December 28 Trump defended H-1B visas.”

This recent debate reveals a deeper question: Why are we still relying on this program after more than 30 years? Is the H-1B visa program solving America’s workforce challenges—or masking our failure to address them?

…

An H-1B visa is a nonimmigrant visa issued by the United States. Nonimmigrant visas apply to individuals wishing to enter the US temporarily. Reasons for entry might include business, temporary work, study, or other reasons.

H-1Bs allow foreign workers to work in specialty occupations in the US for up to six years, with some opportunity to change that six years to permanent residence. Employers that sponsor H-1B holders need specialized knowledge and typically require a bachelor’s degree or equivalent in a relevant field. Common industries employing H-1B workers include technology, engineering, finance, healthcare, and education.

The US Department of Labor says H-1Bs “help employers who cannot otherwise obtain needed business skills and abilities from the U.S. workforce by authorizing the temporary employment of qualified individuals who are not otherwise authorized to work in the United States.”

Proponents and Opponents

Proponents argue that we should expand the number of visas and skilled immigrant workers. They argue that the program is essential to maintaining America’s competitive edge in a global economy, particularly in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. They highlight how skilled foreign workers contribute to innovation, job creation, and economic growth. They note that H-1B visa holders bring expertise in short supply domestically.

They cite studies that find more H-1B workers in an occupation correlate with lower unemployment. That stricter H-1B policies lead US multinational companies to cut domestic jobs while expanding foreign operations, especially in India, China, and Canada. That higher H-1B approval rates lead to more patents, increased patent citations, greater venture capital funding, and higher success rates for IPOs and acquisitions.

Opponents argue the program negatively impacts US workers by depressing wages and reducing job opportunities. They claim some employers exploit the system to hire foreign workers at lower wages, bypassing qualified domestic candidates. Critics point to instances of fraud and abuse, where companies misuse the program to outsource jobs or replace existing American employees.

Opponents further see the program as a failure to invest in the domestic workforce through training and education. They argue that we need to shift our main effort toward equipping US workers with the skills needed for high-demand fields rather than relying on foreign labor.

Now, for our question: So, why do we need more H-1B visas? Or do we?

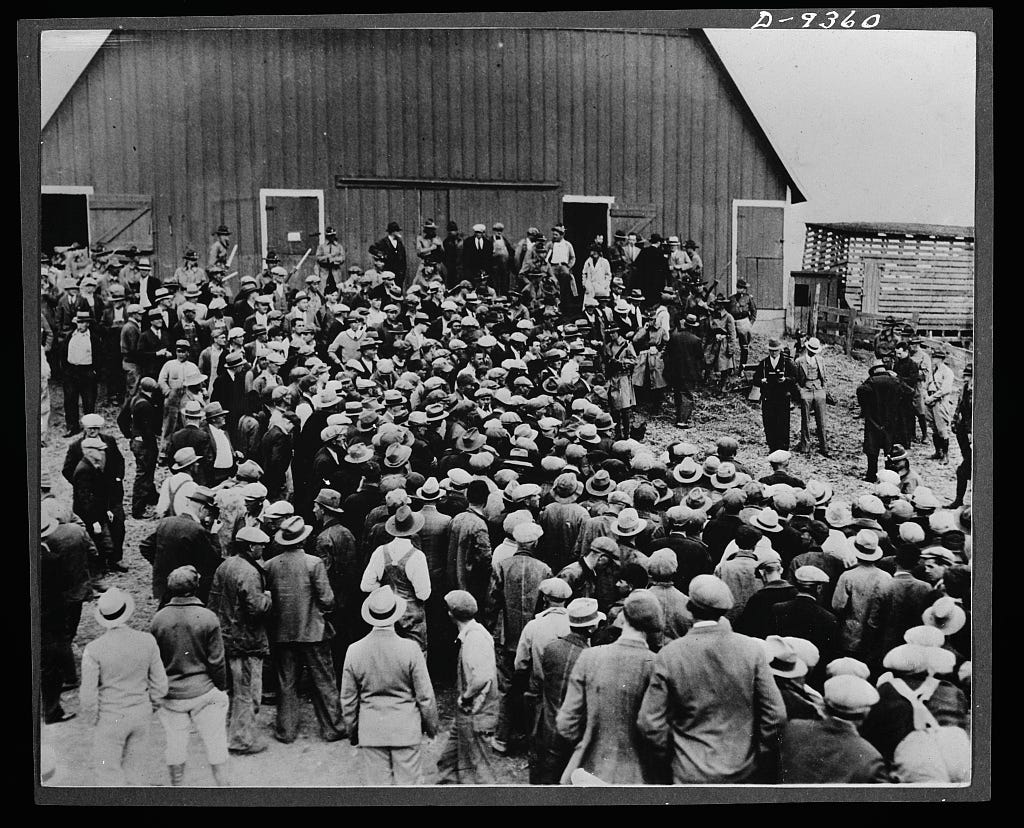

Bipartisan Immigration Efforts in the 1990s

President George H.W. Bush (Republican) signed the Immigration Act of 1990 into law on November 29, 1990. The bill represented the most comprehensive reform of US immigration laws in 66 years. It aimed to adapt national immigration to the American economy’s changing needs. In particular, it addressed the increased demand for skilled professionals in technology, engineering, and other specialized fields.

In 1990, Democrats held a strong majority in the House and Senate. Both parties agreed to increase skilled immigration in support of American business.

One key provision of the 1990 Act was the creation of the H-1B visa category. This effort specifically supported businesses seeking immigrants in “specialty occupations” and required these immigrants to have at least a bachelor’s degree or equivalent in a specialized field of study. The bill intended to enable American businesses to fill critical skill gaps the domestic workforce could not meet.

The law established annual caps on the number of H-1B visas issued, initially set at 65,000. This cap intended to balance employer needs while protecting the domestic labor market. Further, employers seeking skilled immigrants had to attest that hiring foreign workers would not negatively impact US workers by certifying that H-1B workers would be paid at least the prevailing wage for their occupation and location.

…

By 1998, the dot-com boom raged. Tech companies clamored for more skilled workers in STEM fields, and the nation revamped the H-1B program.

But the political tides had turned. The Republican Party held strong majorities in both the Senate and House. No matter. President Bill Clinton (Democrat) signed the American Competitiveness and Workforce Improvement Act (ACWIA) into law on October 21, 1998.

The ACWIA temporarily raised the H-1B cap from 65,000 to 115,000 for 1999 and 2000. It also introduced a training fee for employers sponsoring H-1B workers, initially set at $500 per worker. Congress intended that this fee would fund training and education programs for US workers and reduce reliance on foreign labor in the long term.

…

Employers quickly absorbed skilled workers from the 1998 cap increase, and tech companies returned to Congress a few years later, again asking for more visas. Their request led to another temporary cap increase authorized by the American Competitiveness in the 21st Century Act (AC21) of 2000.

In 2000, Republicans controlled both the Senate and House. President Bill Clinton (Democrat) signed AC21 into law on October 17, 2000. It expanded the number of visas and opened the opportunity for H-1B visa holders to apply for permanent residency.

…

In sum, the tech industry has long demonstrated the need for more skilled labor. Critics argue that this pattern of periodic cap raises reveals structural deficiencies in the training and education of American workers.

Saying this condition is a training and education problem dances around the problem. What we have is a failure to meet Constitutional obligations.

Constitutional Duty

The nation’s guiding document outlines a national purpose to achieve six highly aspirational goals: Union, Justice, Tranquility, Defense, Welfare, and Liberty. These six goals are why the nation exists. Advancing interests not linked to these six goals is meaningless at best and damaging at worst. Two goals—general welfare and justice—apply to our discussion of H-1B visas.

First, general welfare. Individuals can contribute to society when the nation sets conditions to achieve widespread education, healthcare, housing, and safety. Though not the only components of infrastructure, these conditions build the infrastructure that is individual capability. Collective individual capability generates national capability.

Said another way, empowering Americans to contribute to society is an investment in the nation’s infrastructure.

Second, justice. Justice presents the opportunity for Americans from any station of birth to access that infrastructure. Innovation, ideas, and contributions come from every corner of society and lift us all economically and culturally. When Americans from any station of birth can access the infrastructure that supports promoting the general welfare, we strengthen American individuals and businesses.

Expanding the H-1B visa program directly means we have either failed to build the infrastructure that generates individual capability, which then generates national capability, or built the system in such a way that denies Americans the opportunity from any station of birth to access that infrastructure, or both. Therefore, we have failed to achieve welfare and justice, two of our six national goals. Worse, rather than decisive efforts to fix this deficiency, an